Peaks in the Gates of the Arctic National Park, Alaska/George Wuerthner

Editor's note: The following column is from George Wuerthner, who taught Alaskan Environmental Politics as a visiting lecturer at the University of California, Santa Cruz, various field ecology classes for San Francisco State University, University of California Santa Barbara, Prescott College, and environmental writing at the University of Vermont. He was a ranger at the Gates of the Arctic National Park and river ranger on the Fortymile Wild and Scenic River, both in Alaska, and a botanist for the BLM.

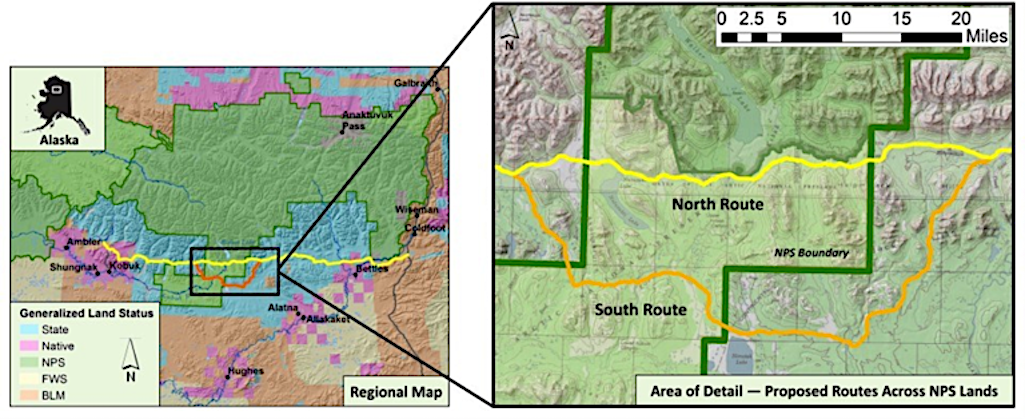

While most Americans were focused on the seditious events in Washington, D.C., the Trump administration approved the right of way for the 211-mile Ambler road across the southern edge of Alaska’s Brooks Range. The route will access mineral deposits near the village of Ambler. The official name is Ambler Mining District Industrial Access Project.

The proposal to drill for oil of the coastal plain of the Arctic Wildlife Refuge has overshadowed the Ambler Road. However, I think the Ambler Road represents a greater threat of long-term ecological damage to the wildlands and wildlife of the Brooks Range than drilling in the Arctic Wildlife Refuge. Though do not interpret this to mean I think oil drilling in the Arctic Wildlife Refuge would be benign.

Among other critical lands, the proposed road, if built, will cross the southern portion of the Gates of the Arctic National Park and Kobuk River Wild and Scenic River.

I lived along the Kobuk River in the 1970s near Shungnak and Kobuk and worked on the Native Claims along the drainage. Later I was a ranger in the Gates of the Arctic National Park and Preserve based out of Bettles, so I am familiar with the landscape and what is at stake if development is permitted to proceed.

The state of Alaska, a staunch advocate of the road, has pledged $37 million to assist in the road construction. Also, the regional native group, NANA, is one of the principal shareholders in the mining project. A number of environmental groups and some native villages have sued the BLM over its decision.

The two main prospects, Arctic and Bornite, contain high-grade copper along with cobalt, zinc, lead, and precious metals. The copper deposits are ten times higher grade than all other copper mines in the world. In other words, these are world-class deposits.

These mineral areas have been known for decades, but mining operations’ main obstacle has been the high transportation cost to its remote location. Even the proposed road is expensive, with an estimated construction cost of $520 million-$1 billion. The Ambler Road would reduce development costs.

In the graphic above, green is national park, blue is state land, and pink is native-owned lands.

The Ambler Road would head west from the Pipeline Haul Road (Dalton Highway). It would pass near Bettles and Evansville villages near its eastern end and terminate among several mining prospects just north of the Kobuk River villages of Ambler, Shungnak, and Kobuk. It will cross 26 miles of the Gates of the Arctic National Park.

The Alaska National Interest Lands Conservation Act (ANILCA), passed in 1980, created many national parks like the Gates of the Arctic National Park. ANILCA had a clause authorizing the road. “Congress finds that there is a need for access for surface transportation purposes across the Western (Kobuk River) unit of the Gates of the Arctic National Preserve (from the Ambler Mining District to the Alaska Pipeline Haul Road), and the Secretary shall permit such access in accordance with the provisions of this subsection.”

The word “shall” almost makes the road’s approval guaranteed.

Ecological Impacts

The road will enable developing these two primary deposits, but the mineralization zone is 70 miles long, and slightly lower grade deposits would be feasible to be exploited. The road will travel across a region that is virtual wilderness and essential wildlife habitat.

The road will intersect almost 3,000 streams and 11 rivers, and three caribou herds’ migratory routes, including the Western Arctic Caribou herd.

There will be numerous gravel mines, construction camps, airstrips, and a fiber optics line located along the entire road during the construction. Radio towers will be placed at strategic locations along the route.

The road will impact many wetlands, often underlain by permafrost, thus changing the hydrology along the road network. It will also cut the Brooks Range slope that will intercept sub-surface flows and concentrate the flow causing more erosion.

Although under current plans, the road will not be open to the public. The same promise was made about the Dalton Highway (Pipeline Haul Road). The mining company claims that since they will be building the road, they can control access; however, there is a chance the state could take over the road if they paid the companies for the investment. If the road is ever opened to the public, one can expect more hunting impacts and a loss of wildlands values.

Caribou may travel up to 9.3 miles to avoid a road. Photo George Wuerthner

Roads can be semi-permeable barriers, and although crossing such obstacles is possible, caribou may shift or entirely abandon seasonal habitat. The disturbance and activity along the road and mining operations are likely to affect caribou in other ways. Studies have shown that caribou may travel up to 9.3 miles to avoid roads and 11.2 miles to avoid settlements.

For instance, a study of the Native-owned Red Dog Mine Industrial Access road north of Kotzebue found that just four vehicles an hour affected the migration of 30 percent of collared caribou or approximately 72,000 individuals of the 2017 population estimates.

Linear features like roads also are used by predators like wolves. This can increase predator influence on prey like caribou. Roads and seismic lines in Alberta have led to increased predation on woodland caribou.

It also does not take much imagination to see that this road will eventually be extended to the coast by Kotzebue, fragmenting the entire western Brooks Range’s ecosystems.

Follow The Money

The proposal to build the road and develop the mineral deposits has the support of some native people. NANA native corporation, which represents Inuit people in Northwest Alaska, owns much of the land surrounding the Ambler Mineral area. NANA is a staunch advocate of the Ambler mine development.

In Alaska, native-owned corporations have a fiduciary obligation to provide dividends to their shareholders. As a result, they tend to support resource exploitation even if some of their shareholders may oppose it. That appears to be the case regarding the Ambler Road, with many villagers in Kobuk, Shungnak, and Ambler opposed to the mining operations.

Like all humans, there are Alaskan natives who generally oppose the industrialization of the landscape and others who are convinced that development will improve their lives.

Indigenous people use modern consumer products, whether cell phones, TVs, boats and outboard motors, snowmobiles, or ATVs. They want their kids to have opportunities to go to college or have something to do in the long, cold winters, so they support the construction of basketball courts, swimming pools, and other facilities that improves their quality of life.

All of this costs money and jobs are in short supply in remote villages.

One can be sympathetic to their support of jobs and development like the Ambler Mines that will likely provide greater financial security.

One way to understand who supports or opposes the road is to examine the flow of money. There are numerous Alaskan mining operations, currently in the permit process or proposed, where native people are stockholders. These include the proposed Pebble Mine in Bristol Bay, the Red Dog Mine in NW Alaska, and Goodpasture mine in Interior Alaska.

During the land selection process created by the Alaska Native Claims Settlement Act (ANCSA), native people targeted the lands that held valuable known mineralization or fossil fuel resources.

In the case of the Ambler mines, NANA shareholders are likely to be employed during road construction and mining operations. One study estimates that 20 percent of all construction jobs will be held by local villagers, providing a significant input of money into these rural villages. NANA corporate leaders likely believe they are working in the best interests of their constituency.

However, the Tanana Chiefs and residents of the villages of Huslia, Alatna, Allakakat, Evansville, and Tanana, oppose the road.

These people are Dene or Athabaskan Indians represented by Doyon Corporation. They are opposing the road and mining since they believe the Ambler Road will harm their subsistence activities as well as how industrialization might alter the entire culture of the villages.

Yet Doyon Corporation, which represents the Athabaskans of Interior Alaska including the Gwitch In who are opposed to drilling in the Arctic National Wildlife Refuge, have several mining operations in the state. During the land selection process, Doyon specifically targeted mineralized lands. Today, they have several active mining operations.

They also have on-going oil and gas development.

The good news is that a number of conservation groups and native allies are suing to stop the Ambler Road construction. The construction costs are enormous and may still preclude road and mining development.

We shouldn’t let the efforts to protect the Arctic Wildlife Refuge take our eye away from other potentially destructive developments like the Amber Road. For more than 50 years, some Alaskans have dreamed about developing the rich ore deposits of the Ambler Mining District. With luck maybe we can still keep them dreaming. One can hope that the Biden administration will nick the road permit and put to rest this potential damage to the wildlands of the southern Brooks Range.

You can submit comments to the National Park Service by February 15th.

George Wuerthner recently worked as Ecological Projects director for the Foundation for Deep Ecology and Tompkins Conservation, promoting parks in Patagonia and elsewhere. Wuerthner taught as a visiting lecturer Alaskan Environmental Politics at the University of California, Santa Cruz, various field ecology classes for San Francisco State University, University of California Santa Barbara, Prescott College, and environmental writing at the University of Vermont. He was a ranger at the Gates of the Arctic National Park and river ranger on the Fortymile Wild and Scenic River, both in Alaska, and a botanist for the BLM.

Add comment