President Franklin Roosevelt visited with CCC enrollees near Camp Roosevelt on August 12, 1933, at Big Meadows in Shenandoah National Park, Virginia. Seated from left are Maj. Gen. Paul B. Malone, Louis M. Howe, Harold L. Ickes, Robert Fechner, FDR, Henry A. Wallace, and Rexford Tugwell./National Archives

The year 1933 found the United States in the grip of the Great Depression. Millions of young men were jobless, their prospects grim. Seventeen days after his inauguration, President Franklin Delano Roosevelt sent a message to Congress urging creation of a Civilian Conservation Corps to employ jobless young men in conservation work on public land.

This federal work relief program, in the ten years of its life, put 3 million young men to work on projects aimed at “conservation and development of the natural resources of the United States.” The CCCs planted billions of trees, built infrastructure in national parks and forests including campgrounds, trails, and roads. They constructed fire lookouts and strung wires connecting them to ranger stations. They fought forest fires. The U.S. Army established camps to house recruits across the country, and the young men received $1 per day, regular meals, housing, and access to education.

The National Park Service director at this time was Horace Albright, who was a close confidant of Roosevelt’s Secretary of the Interior, Harold Ickes, who appointed him as Interior’s representative on the CCC Council that set up the CCC program. With this inside track, Albright’s agency was quickly ready with projects, and thus the National Park Service became a great beneficiary of the CCC program. Some argue that the boost from the CCC and other New Deal programs cemented the institution of national parks and the National Park Service in American life.

At the outset of 2021, the situation is different in many ways from that of 1933, but there are similarities. One is that there are many unemployed men and women in need of work and income. Another is that the National Park System (and the environment at large) has many needs that must be addressed. Yet another is that the country is in a period of crisis caused by COVID-19 and a federal administration that has done everything in its power to advance energy development and other interests at the expense of public land conservation.

The CCC and other New Deal programs brought a huge infusion of resources to the National Park Service, and recent passage of the Great American Outdoors Act promises the same to address needs of the National Park System today.

A CCC camp at Skyland in Shenandoah National Park/NPS archives

While some of the conservation challenges of 2021 for the nation and the National Park Service are the same as in 1933, many are new and different. Unemployment and the need for federal response are similar but causes differ. In the 1930s the conservation challenges were deforestation, soil erosion, lack of infrastructure in new national forest and park systems in the face of growing outdoor recreation, a policy of wildfire suppression also needing infrastructure like trails and fire lookouts.

Needs today that might be the focus of a renewed CCC-type of initiative include infrastructure work, but also responses to climate change, measures to stem loss of biodiversity, reduction of impact of invasive species, management to restore the ecological role of wildfire, and restoration of ecological processes, among many other environmental problems associated with growing population pressure and development.

So, here we are in 2021 and the idea of a large Federal Conservation Corps program is emerging in Congress and elsewhere. President-elect Biden has called, during his campaign, for “the next generation of conservation and resilience workers through a Civilian Climate Corps.” Vice-President-Elect Harris as a senator co-sponsored legislation titled Cultivating Opportunity and Response to the Pandemic through Service (CORPS) Act, which proposes to greatly increase service opportunities nationwide over the next three years for unemployed youth.

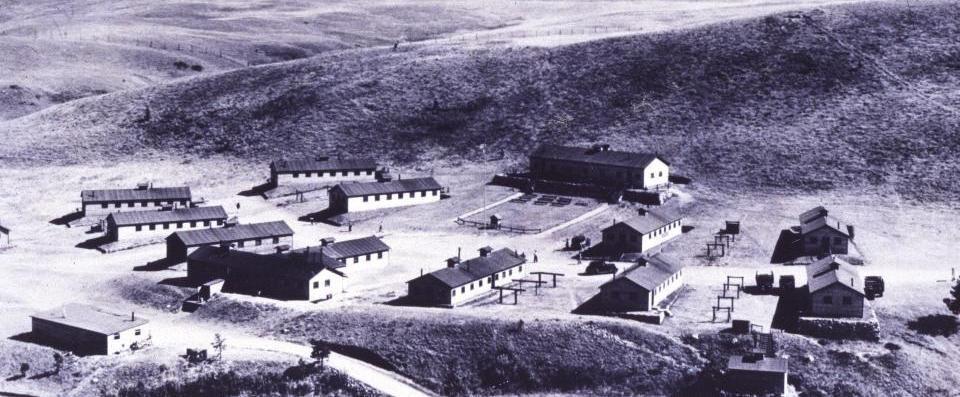

A CCC camp in Wind Cave National Park/NPS archives

Senator Martin Heinrich (D-NM) introduced the Pandemic Response and Opportunity Through National Service Act and pushed for inclusion of a corps program as part of the Great American Outdoors Act. Senator Ron Wyden (D-OR) introduced the 21st Century Conservation Corps for our Health and Our Jobs Act, and Senator Dick Durbin (D-IL) introduced the RENEW Conservation Corps Act, also introduced in the House by Representative Joe Neguse (D-CO).

None of these bills gained traction during the 116th Congress – note that all have been introduced by Democrats – and the lack of any bipartisan support has slowed any progress on this and most legislation in this Congress. Still, all of these legislative initiatives indicate that the idea of national service programs like the CCC aimed at job creation and environmental conservation was on many minds late last year.

The conservation corps idea has reemerged in various forms since the original CCC. WWII ended the original program, but in 1953 a student at Vassar College was looking for a senior thesis idea and decided to make the case for a student conservation corps which might for her be more than an academic exercise. Elizabeth Cushman found a supportive adviser, met with people at the National Park Service and the National Parks Association, and successfully established what ultimately became the Student Conservation Association. Its first recruits worked during the summer of 1956 in Grand Teton and Olympic national parks under the auspices of the National Parks Association. The SCA under Cushman’s leadership grew over the next decade and expanded into many national parks. Cushman’s program was a non-profit organization, in the private sector, but eventually led to a federal government program called the Youth Conservation Corps (YCC).

CCC crews and mules hauling equipment at Haleakalā National Park/NPS archives

As the SCA established itself during the 1960s, the federal government launched a “war on poverty,” part of which was an effort to provide opportunities for young people who were dropping out of school and even being rejected by the military draft. The Job Corps was established in 1965, one part of which were Job Corps Civilian Centers administered by the Park Service and Forest Service. The emphasis was on job training, which had not been the focus of the SCA, and the job training was on public land conservation projects.

One of the most powerful members of Congress at this time was Senator Henry M. Jackson of Washington, and in the late 1960s he visited an SCA high school program in Olympic National Park. Jackson had been interested in the idea of a federal program like the SCA for a decade and had unsuccessfully proposed legislation to create one. Inspired by what he saw at Olympic where a lot of work was getting done and young people were thriving, Senator Jackson went back to the legislative well and in August 1970 President Richard Nixon signed legislation Jackson championed to authorize a pilot program that became “permanent” in 1972.

Under that program young people (aged 15-18) worked for 8-10 weeks in summer on conservation-related projects on public lands administered by the Departments of Interior and Agriculture. Many projects were in units of the National Park System. Enrollment in YCC peaked in 1978 with 46,000 enrollees, and in its first decade provided an opportunity for more than 200,000 young people to “earn while they learn.”

Expanding on YCC, Congress established the Young Adult Conservation Corps (YACC) in 1977, a year-long program for enrollees 16 to 23 years of age also administered by the Departments of Interior and Agriculture in cooperation with the Department of Labor. They were “to carry out projects on Federal or non-Federal public lands and waters,” and part of the funding was directed to state and local levels. Funding for both programs was curtailed in the early days of the Reagan administration, but YCC, which was a success in many ways, did not disappear. Limited programs continued up to the present in national parks and other public lands – the National Park Service reported 722 participants in YCC programs for fiscal year 2019.

The Park Service and other agencies carried on with YCC at small scales, and in 1993 another iteration of conservation corps was established by Congress that continues to the present – the Public Lands Corps (PLC). This authorizes Interior and Agriculture to hire young adults as job training to engage in projects for conservation, restoration, construction, or rehabilitation of resources on “eligible service lands.”

In this case, “disadvantaged” young people may be given preference, and agencies are authorized to enter into cooperative agreements with nonfederal organizations in which the federal agency provides 75 percent of project costs with 25 percent coming from nonfederal sources. Participants in the PLC Resource Assistant Program, after completing a degree, may become eligible for direct appointment to a position for which they are qualified in a federal conservation agency – a way to attract new talent to federal conservation agencies. The National Park Service reported in 2019 that it had hired 6,145 participants through “youth serving partner organizations” without specifying how many were under the auspices of the PLC.

All of this reveals that the conservation corps concept has survived in the federal public land bureaucracy, but at a relatively small scale. In 2012 the Obama administration established the 21st Century Conservation Service Corps Initiative (21CSC) to expand opportunities for youth employment and training on public lands and waters, but did so without legislative authority. A large array of programs fell under the 21CSC, but the initiative did not hatch new programs. As the federal government has stopped and started these conservation corps programs, the CCC model has evolved new dimensions elsewhere.

Civilian Conservation Corps crews worked in the landscape that evolved into Cuyahoga Valley National Park in Ohio/Archives

States recognized the value of the youth conservation corps, beginning with California in 1976, and by the mid-1980s, after the demise of the federal YCC, nine states followed California’s lead. California established the first Urban Conservation Corps in 1983, soon followed by New York City. State and local corps appeared across the country, and in the 1990s targeted federal funding for these programs became available through the Youth Service Corps Act of 1990 and the National Service Trust Act of 1993.

AmeriCorps provided a new source of funds in support of many community service programs, some of which addressed conservation. Two decades into the 21st century, the CCC model in its various iterations and with an ethic of service focused on conservation is very much alive. A National Association of Service and Conservation Corps in 2020 counted 135 service programs in its roster of locally based organizations.

This historical overview of the conservation corps model reveals how it has been adapted to changing political, economic, and environmental situations over nearly a century. These programs have and continue to address many needs in the United States, too many to explore comprehensively here.

Let us now turn to how a 21st Conservation, Climate and Environmental Corps, or whatever it should be called, might serve the country and especially the National Park System over the next several decades. Senator Dick Durbin (D-IL) introduced the RENEW Conservation Corps Act in September 2020 in the 116th Congress, naming the Corps the “Restore Employment in Natural and Environmental Work Conservation Corps;” not quite as succinct for an acronym as CCC, but descriptive of the intent of the legislation.

His bill suggested some of the features a new version of the CCC might include. Projects under the purview of the Departments of Interior and Agriculture would be funded. Goals of the bill were to put people unemployed because of the economic impact of the pandemic and other dislocations to work and to invest in fish, wildlife, and habitat restoration, and in outdoor recreation infrastructure. Other goals are to tackle green infrastructure maintenance backlogs and provide education and skill-development opportunities in conservation fields.

The bill offered a long list of projects that would be eligible for funding, including projects to plant trees, restore and manage wildlife habitat; control invasive species; conduct prescribed burns; restore streams, wetlands, and other aquatic systems; and ten more. The legislation would provide resources to the existing network of conservation corps and support employment of one million people during the five years following enactment of the legislation.

CCC crews worked in the forests of Rocky Mountain National Park/NPS archives

This bill cited the many needs such legislation might address, specifically “dedicated conservation land projects to support the growing backlog of deferred conservation land projects,” which would involve all federal conservation agencies, but particularly the National Park Service, which has a well-documented and publicized maintenance backlog.

The NPS also has a funding source for such work established this past fall by passage of the Great American Outdoors Act. I cite this bill because it describes more of the potentials of such corps legislation than other recent proposals and is closer to the CCC model than many of them. For instance, it is directed specifically at investments in the outdoor recreation economy, which is growing fast on public lands in the West.

In addition to providing jobs and addressing physical and environmental needs, such a progrm would “prepare the individuals for permanent jobs in the conservation field,” and “expose Participants to public service while furthering the understanding and appreciation of the Participants of the natural and cultural resources of the United States.”

A Conservation Corps Act like this will, as has been demonstrated by the earlier iterations of the model, have many outcomes in addition to the obvious jobs created, infrastructure built, and environmental problems addressed. There will be many educational and personal growth outcomes, diverse young women and men from urban and rural backgrounds working together, building ethics of cooperation and of service, experiencing people and places once beyond their imaginations.

As their work focuses on repairing environmental damage and otherwise addressing environmental problems, they will become more aware of the natural environment and why it must be conserved. Their social and environmental appreciation will grow. They will learn the nature of meaningful work and be serving the country, learning to see themselves as stewards of their environment and especially the American public lands legacy.

The bottom line is that corps programs are of proven value – we know they produce positive outcomes – economic outcomes like jobs, support for the rapidly growing outdoor recreation economy, training and work experience. Social outcomes like bringing young people together and helping bridge divides in American society. Educational and personal growth outcomes as, for instance, the educational stipends awarded Americorps enrollees and the environmental education mandated as part of the federal Youth Conservation Corps. Environmental outcomes like streams restored, trees planted, trails constructed and maintained, invasive species removed, and much more.

A national investment in programs like these is an investment in both social and natural capital that has and will pay great dividends into the future.

Would a conservation corps like that proposed by Senator Durbin really be of much help to the National Park Service in its current situation of its maintenance backlog and other challenges? This is a fair question. The NPS website states that “(M)ore than $11 billion of repairs or maintenance on roads, buildings, utility systems, and other structure and facilities across the National Park System has been postponed for more than a year due to budget constraints. Collectively those projects are known as ‘deferred maintenance.’”

Of deferred maintenance the NPS estimates that, as of 2018, paved roads and structures accounted for $6.15 billion of the backlog, other facilities to $5.77 billion. While much of this work on roads, bridges, buildings, wastewater systems, utility systems and other infrastructure would be beyond young people and need to be done by seasoned professionals, trail work and more directly environmental conservation projects would be within their reach.

Does the National Park System need help with environmental projects like those listed in Senator Durbin’s legislation that fall outside their definition of deferred maintenance? Undoubtedly it does – its core mission is stated as “preserve parks and provide world-class visitor experience.” Work on deferred maintenance prioritizes the latter, but at the same time, at least in the parks where nature is the paramount attraction (as opposed to culturally focused units of the system), environmental conservation needs are many. Perhaps some of the maintenance needs not requiring a high level of technical expertise could be served by corps enrollees, but their principal contribution will likely be in environmental conservation.

Much planning and thought will certainly be required to incorporate conservation corps workers into national park projects. When I was supervising YCC projects in North Cascades and Olympic national parks back in the 1970s, teenagers, mostly city dwellers, did remarkable work under the instruction and watchful oversight of NPS professionals. Small bridges and other structures were constructed, trails built and upgraded. The professionals might have preferred to just get the job done and not have to deal with youthful laborers, but most were patient and effective teachers, and the jobs were completed. The young people enjoyed a great national park and educational experience.

Another question that plagues anyone thinking about scaling up corps programs today is whether doing so is politically feasible. In the current divisive political environment not much has moved through the Congress, the Great American Outdoors Act being an exception due to presidential politics and very strong support by the American people for action on deteriorating national parks. As the Act moved toward action New Mexico’s Senator Martin Heinrich, the first Americorps alum to serve in the Senate, and some of his colleagues, sought to include a provision in the legislation that would allocate funding for national park work to a program on the corps model.

That provision didn’t make it into the final version of the bill signed by President Trump. While the corps idea is getting increased attention, most of that is coming from Democrats, and the future of any such legislation is politically uncertain.

Despite the difficulties of the political environment recently, which may change with a Biden administration, the time is right to advocate for the conservation corps idea. A campaign for a new corps program to provide jobs for young people, to address pressing problems arising from climate change and environmental degradation, to especially address needs and opportunities to improve public lands like national parks, and to provide one vehicle for national service, must be mounted and can accomplish much good on many fronts.

The foundation for such action today has been laid over the past 90 years. The time for a 21st Century Climate and Conservation Corps is now.

Comments

My father was a part of the CCC, born to Irish Immigrants in Hell's Kitchen, he spoke glowingly of his opportunity to work in the National Park System in the Pacific Northwest. It transformed his life and aspirations . Count me in for help to call our legislators in the next Congress. Great article.Thank you.

Excellent piece, John, thanks for this in-depth look at the C.C.C. and its successor programs. I spent many of my younger days hiking the trails those guys blazed in the Northwest forests. There's no lack of work to be done today, either, but I hope that any program that is devised will focus on restoration of degraded streams, forest lands, and grasslands, as well as maintenance of existing trails. I'm concerned that it not become a kind of Mission 66 for new recreational infrastructure, such as building new trails in wildland areas which will increase conflicts with wildlife and introduce human impacts into isolated areas. Unfortunately any new federal program tends to be regarded as a money pot for everyone's pet projects.

Yes, it's true that "any new federal program tends to be regarded as a money pot for everyone's pet projects." However, the article also indicates that, "President-elect Biden has called, during his campaign, for 'the next generation of conservation and resilience workers through a Civilian Climate Corps.' Vice-President-Elect Harris as a senator co-sponsored legislation titled Cultivating Opportunity and Response to the Pandemic through Service (CORPS) Act, which proposes to greatly increase service opportunities nationwide over the next three years for unemployed youth. Senator Martin Heinrich (D-NM) introduced the Pandemic Response and Opportunity Through National Service Act and pushed for inclusion of a corps program as part of the Great American Outdoors Act. Senator Ron Wyden (D-OR) introduced the 21st Century Conservation Corps for our Health and Our Jobs Act, and Senator Dick Durbin (D-IL) introduced the RENEW Conservation Corps Act, also introduced in the House by Representative Joe Neguse (D-CO). None of these bills gained traction during the 116th Congress - note that all have been introduced by Democrats - and the lack of any bipartisan support has slowed any progress on this and most legislation in this Congress." It's would also be good to note that the original Civilian Conservation Corps (CCC) was pushed through by a Democrat, President Franklin Delano Roosevelt, who proposed it only seventeen days after his eventual first inauguration in 1933 ...and that was back in the days of manual typewriters when it was difficult to even reproduce such proposals for distribution.

I refer to it as FDR's "eventual" first inauguration in 1933 because, even after Herbert Hoover's stubborn and catastrophic incompetence led to the collapse of 1929 and resulted in the Great Depression and even after FDR defeated Hoover in that subsequent election in the fall of 1932, Hoover refused to concede that election, refused to cooperate in the transition to FDR's first term. Hoover's obstruction hindered FDR's ability to quickly mobilize responses to the deepening depression, all of which makes FDR's ability field a cogent proposal for the original CCC all the more impressive. Despite the abject failure of Hoover's rightwing approaches to governance in the years running up to the Great Depression, FDR had to continue fighting rightwing resistance, up to and including politicians and influencers sympathetic to overtly fascist regimes in Europe, during all of his many terms in office.

And, it also needs to be noted that, as I have pointed out before, those of us in the authentic conservation movement who truly love our public lands and national parks continue to be undermined and bedeviled by ultra-rightwing, anti-government, highly partisan lobbying today. One of these lobbying operations, based in Bozeman, generally tries to pose as a "hook-and-bullet" level of conservation group. But, it actually remains what it's always been, a well, but invisibly, funded ultra-rightwing anti-government cadre championing laissez faire, free market approaches to environmental and conservation issues, believing that the use of commercial business models, everywhere, will automatically improve environmental quality and opposing both environmental protection regulations and most tax funding for conservation. This group has had at least a couple of names since its birth during the heyday of one of its leading lights, the notoriously destructive James Watt; but, it's currently calling itself the Property and Environment Research Center (PERC) and it remains firmly focused on and dedicated to opposing, weakening, or just flat dismantling any and all regulations designed to protect the environment, including laws protecting our public lands and national parks.

Over the years, Terry Anderson, one of PERC's founders, past presidents, and revered icons, has been enshrined as a Fellow of the Hoover Institution, another ultra-rightwing think tank essentially and quite inappropriately hosted and sponsored by Stanford University. As I've pointed out before, the Hoover Institution website displays Terry Anderson's photograph right next to the photograph of Scott Atlas, once a radiologist who has since become an ultra-rightwing Hoover Institution political pundit. Scott Atlas is that guy who unilaterally assigned himself nebulous qualifications and expertise as an epidemiologist and, blinded by his own ambition, elbowed Dr. Anthony Fauci aside and assumed the position of public health advisor to that reckless and intellectually impaired would-be monarch who incited yesterday's armed assault on our House, Senate, and Capitol. Scott Atlas, Fellow of the Hoover Institution, then stood by and watched, giving credence to Trump, as solid medical science was replaced with a childlike version of a "herd immunity" approach to our COVID-19 problem. In doing so, Scott Atlas helped pave the way for the needless deaths of hundreds of thousands of our fellow citizens. Again, Scott Atlas and PERC's Terry Anderson are both Fellows of the Hoover Institution, which is dedicated to the infamous Herbert Hoover, father of the Great Depression and the election loser who then tried to stand in the way of FDR's CCC and other programs. The continued connection between the Hoover Institution and Stanford University demonstrates that, for Stanford, money and connections are higher priorities than either ethics or genuine intellectual merit and Stanford's alumni and donors should ask why.

I also note 1933 as the year of FDR's "eventual" first inauguration because 1933 was an important year. The year 1933 is important because it connects one of our worst presidents, Republican Herbert Hoover, and the Great Depression; one of our greatest presidents, Democrat Franklin Delano Roosevelt, and the original CCC; the infamous ultra-rightwing Hoover Institution; that ultra-rightwing, anti-government, highly partisan lobbying operation, PERC; and one of the worst outcomes of the vile antics that have been undermining and bedeviling those of us in the authentic conservation movement who truly love our public lands and national parks. You see; 1933 is also when the old Yellowstone Association (YA) began operations in support of the National Park Service mission in Yellowstone National Park.

The old Yellowstone Association was a real conservation group, genuinely dedicated to supporting and protecting the park, its environment, and its wildlife and, over time and under its management, its Yellowstone Institute became globally respected and influential; but, not everyone liked that. Some of those ultra-rightwing political partisans associated with PERC didn't and, as their influence grew stronger within a more recently formed fundraising group called the Yellowstone Park Foundation, questions were soon raised about the allegedly wasteful redundancy of two major nonprofits supporting the park in parallel. As would be expected given PERC's ultra-rightwing rhetoric, they argued that they, now influential within the Yellowstone Park Foundation, could bring higher levels of business, retail, and fundraising expertise to a new, larger, merged organization and more efficiently manage what was then being operated by the old YA. The propaganda barrage worked. By the fall of 2016, just prior to the Trump takeover, the nonprofit Yellowstone Forever (YF) was created in a seemingly unfriendly, some say forced, merger of the old YA with the more recently formed Yellowstone Park Foundation. By the time of the merger, the old YA had been successfully working on behalf of Yellowstone National Park since 1933 and had successfully run the Yellowstone Institute since 1976, so successfully that it brought over $13 million in net assets into that merger, while the Yellowstone Park Foundation brought only half that amount. Again, the old YA had been working successfully on behalf of Yellowstone National Park since 1933 and had successfully run the Yellowstone Institute since 1976; yet, despite the allegedly higher levels of business, retail, and fundraising expertise that the Yellowstone Park Foundation was going to provide, the newly merged Yellowstone Forever (YF) wrecked itself in less than four years, blaming financial difficulties for the closing of the Yellowstone Institute in the spring of 2020. In hindsight, the influence of PERC's ultra-rightwing rhetoric, the end result of that hollow, but much ballyhooed, laissez faire, free market approach to environmental and conservation issues, the outcome of that belief that the use of commercial business models, everywhere, would automatically improve environmental quality, the upshot of all that smarmy opposition to both environmental protection regulations and most tax funding for conservation was just as worthlessly and needlessly destructive as the contribution of Scott Atlas and the Hoover Institution to our COVID-19 response. It did nothing more than bankrupt one of America's great conservation organizations, silence the Yellowstone Institute, disrupt the conservation support services being provided, and deceitfully serve to discredit the values these historic citizen science and conservation entities represented. And Yellowstone National Park was left in the lurch.

So, where do we go at this point? Well, first, we need to wholeheartedly support our incoming federal administration in its efforts to use a reenvisioned CCC as part of our approach to continuing to repair the economic wreckage left by the last two republican administrations. Second, we need to oppose the disingenuous propaganda being spewed by and the deceitful influences of ultra-rightwing, anti-government, highly partisan groups like PERC and the politicians hiding behind the curtains and supporting them. Third, as I have tried to illuminate the broader connections, the historic connections, between the challenges we face today, we need to continue to investigate, reveal, and understand those connections. The original CCC was born despite rightwing obstructions and opposition; PERC was born during the heyday of one of its leading lights, the notoriously destructive James Watt; PERC's revered icon, Terry Anderson, is enshrined, along with Trump henchman Scott Atlas, as a Fellow of the infamous ultra-rightwing Hoover Institution; and the old Yellowstone Association, which had been working successfully on behalf of Yellowstone National Park since 1933 and had successfully run the Yellowstone Institute since 1976, disappeared in and was ultimately destroyed by a seemingly unfriendly, some say forced, merger in the fall of 2016, just prior to the Trump takeover and as ultra-rightwing out-of-state politicians were buying their way into Montana politics. What are the connections? There is now an uptick in and intensification of the activities of ultra-rigthtwing groups, including PERC. Why now? Is it really because Gianforte, Daines, and their money actually did buy the entire State of Montana in this last election? If so, what is the full extent of the continuing connections between Gianforte, Daines, and other ultra-rightwingers and PERC, Yellowstone Forever, the National Park Service, and even things as mundane as the future of bison conservation? And, fourth, there a current saying that progressives tend to engage in pillow fights while the rightwing takes headshots. Well, just a few days ago, there was an apparently long planned and carefully orchestrated ultra-rightwing attempt to violently overthrow the government of the United States, an attempt that included a direct, carefully planned, and deceitfully orchestrated armed assault on our House, Senate, and Capitol; yet, even now, we're hearing the usual calls to let bygones be bygones in the name of some delusional notion of national unity. I, for one, believe we need, especially at this moment, to honor our moral and ethical guideposts and the rule of law. We don't need to sugarcoat. We don't need to let villains off lightly. We need to speak the truth and hold villains accountable. We no longer need or should suffer fools or put up with immaturity and there need to be consequences.

Sounds like a wonderful solution. But where are you going to find the workforce. Very few of the 18-35 year olds capable of this work have the work ethic to do it. Manual labor would be required. Make it a path to citizenship for those that would do the work, and it might be viable. Few, capable of doing this type work, are hungry, living in poverty, wondering where there next meal is coming from; like the majority of the original CCC workers. My dad was part of the CCC, and was forever grateful for boost it gave him.

Pre-covid, employers were struggling to fill jobs as it was and we had an employment level many experts had said would be impossible to achieve. It is hard to predict what employment needs will be once everything is open again but the last thing we need are more taxpayer funded jobs, particularly given the enormous debt we have taken on. Now if you would make a civilian jobs program a requirement for those already receiving government / taxpayer assistance I'd support that.

HUMP:TL/dr

Just wondering, Wild, what your similar requirement was in payback for the government assistance/benefits/services (i.e. highways, airports, mail service, internet, phone, schools, police, military, courts, public transportation, electricity, water, etc.) you've received over your lifetime?

Probably paying significant taxes and user fees.