President Theodore Roosevelt stood on the rim of the Grand Canyon in 1903 and addressed a crowd of curious Arizonans. “Leave it as it is,” he said. “You cannot improve upon it. The ages have been at work on it, and man can only mar it. What you can do is keep it for your children, your children’s children, and for all who come after you, as one of the great sights which every American if he can travel should see.”

Of this historic moment, David Gessner writes, “While the crowd is delighted that the president of the United States is here, not everyone is pleased with the message. The enemies of the message then are the same enemies of the message now. Locals thinking in the short term. Entrepreneurs trying to make a buck off a big hole. Ranchers and miners. Extractors.” This moment, Gessner writes, “is the opening shot in a war still going strong over a century later.”

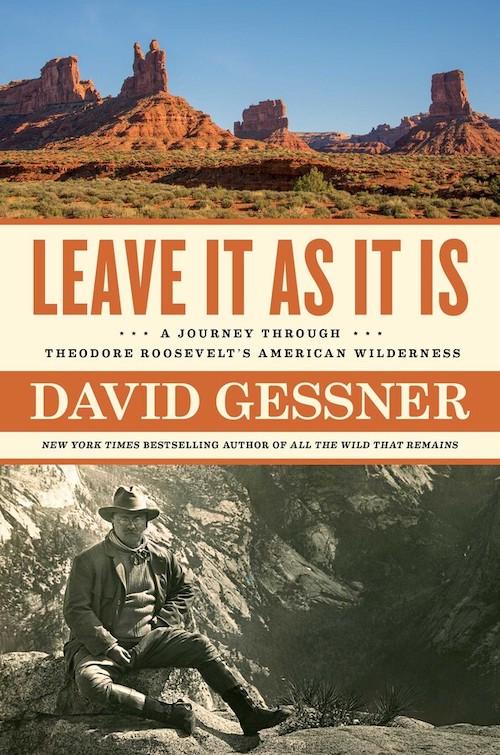

The “war” Gessner alludes to is, of course, over the use of public lands of the United States, whether they be exceptionally unique and scenic places like the Grand Canyon, or rangeland across the West. In Leave It As It Is Gessner embarks on journeys across the American West, informed by the words and deeds of Teddy Roosevelt, to dig deeply into how Americans have responded to his preservationist idea over the nearly 120 years since Roosevelt made that speech. Gessner didn’t set out to write a biography but “after years of writing about nature I wanted to begin to fight for it. And in that effort I couldn’t think of a better role model than Theodore Roosevelt.”

Gessner visits many places across the West: Badlands National Park, Yellowstone National Park, Muir Woods National Monument, Yosemite National Park, Grand Canyon National Park, Bears Ears – especially Bears Ears. He talks with many people along the way, quoting them liberally: Regina Lopez-Whiteskunk of the Ute Mountain Ute, Navahos James Adakai and Kenneth and Mark Maryboy, Bluff, Utah, archaeologist and guide Vaughn Hadenfeldt, Utah politician and opponent of Bears Ears National Monument Phil Lyman, and many others. He quotes from Teddy Roosevelt, Bernard DeVoto, and other writers and participants in the history of public lands. And he shares stories of his personal encounters with Western places and characters.

Gessner addresses several issues in this book. Is it possible to leave any place “as it is?” How do we reconcile good guy conservationist Roosevelt with the hunter and someone who thought “extermination of the buffalo was the only way of solving the Indian question” as he wrote in his book Hunting Trips of a Ranchman? Gessner asks, after reviewing ecomodernist criticism of the idea of preservation and of wilderness, “Am I simply clinging to an old romantic narrative based on a lie? Add the doom of climate change to the mix and why fight for wilderness at all?” Why are disagreements over public lands so fraught and what can, and should, we do to defend this shared American legacy? In particular, why should we fight to restore Bears Ears National Monument, drastically reduced by the Trump administration?

Gessner answers these questions and more in Leave It As It Is. He deconstructs the phrase “as it is,” admitting that the idea that any place like the Grand Canyon “was a pristine ideal of an unpeopled nature” was uninformed romanticism. But does that mean there is no real wilderness? After considerable discussion of the ecomodernist critique of wilderness he writes that we should be critical of Teddy Roosevelt and other early conservationists, “But while we are being critical of Roosevelt and others for not stepping out of their time, we should not fail to step out of our own.”

Roosevelt’s work led to national parks and he liberally used the Antiquities Act as a preservation tool, for which he is criticized by the ecomodernists. But Gessner notes that today we are “guilty of our own brand of biocide” and argues that “Ecomodernists can sneer at parks if they like, but without them and the habitats they provide, thousands more species would have been lost. If it was an idea mired in the prejudices of its time, it was also one that looked beyond those prejudices to the future.” This leads him to reflections on the value of parks and wilderness, to the potential of connecting them and thus providing avenues for wildlife to survive in the age of climate change.

For all the talk of ecomodernist critics, only one way exists to preserve biodiversity and large species, and fend off further extinction, and that is not just conserving large swaths of wild land but connecting those swaths. Large animals thrive in wilderness, not labs. Preservation may be a dirty word, but all the technology and market analysis in the world cannot rebuild what billions of years of evolution have created.

In his final shot in this argument Gessner writes “for the postmodern theorists who doubt whether or not wilderness still exists I would recommend a week in the backcountry of Y2Y [Yellowstone to Yukon], hanging out on a mountain ridge in the snow with grizzlies and wolverines. They would learn quickly that the earth is still wild.”

Gessner’s answer to the question of why fight for public land and wilderness is addressed throughout the book and has too many elements to easily summarize, but one of those arguments relates to his point above about biodiversity and extinction.

Adaptability – that is, evolution – is necessary in times of crisis. When we cut off possibilities, we cut off our chances of survival. We cut off the escape route of evolution. That is why we need to fight for these lands to our last breath. Because if we continue to protect our parks, monuments, and forests, and maybe connect and expand them, something both everyday and miraculous will occur: evolution will keep on working.

This is the long view. Elsewhere he adds, “What if, instead of packing it in and saying the world is screwed and cultivating our tiny gardens, we turn it around and embrace the idea of not giving up on the wild.” He observes “If we behave poorly, the gifts of nature we have now will not be handed down to our grandchildren.” Reflecting on the value of forests toward the end of the book he asks, “Is it crazy to suggest, in this age of drought and megafires, that what we ought to do is protect them and their earth-saving ability to store carbon against any interest group other than the greater good, and rather than sell them off, we should fight to preserve them with all we have? That rather than reduce and diminish, we should expand and protect.” Throughout the book Gessner makes compelling arguments for fighting the fight.

What does Gessner suggest be done to protect public lands from those who would “return” them to the states that never had them and would likely sell them into private ownership, and from those like Cliven Bundy who claim a property right to public land they use, in Bundy’s case without paying even the minimal grazing fees required by the government? He describes an alternative to privatization and continued degradation.

The alternate route is connectedness and the imagining of a great and healthy pathway. Restoration of those lands is visionary and may seem impossible in these times. But the proof that we could do it now is that we did the impossible in the past. No one had heard of national parks when we decided to create them. Wouldn’t it be nice if a century from now someone said the same about migratory pathways and restored ecosystems along the continent’s spine?”

There would be opposition to such an initiative, even violent opposition. “True,” he writes, “a few cowboys would be angry at us if we told them their cows had to be restricted to land they actually own, and they might even shoot at us. But maybe it is still worth it. The choice is ours. To reclaim the lands that we own or to shrug and walk away.” Strong stuff, but as Gessner said earlier, he wants to become a fighter, and these are fighting words.

His travels convince him that the most urgent fight is for restoration of Bears Ears National Monument established by President Obama and eviscerated by President Trump. After discussion of the Antiquities Act which Teddy Roosevelt advocated for and used, he focuses on Bears Ears. He makes the case that if ever there was an area of public land that fit the intent of the Antiquities Act, it is Bears Ears. Archaeologist Vaugh Hadenfeldt makes the case, as he and Gessner visit Cedar Mesa, that the place is monumental in its archaeological richness. It is rich in anthropology, archaeology, geology, and paleontology. Gessner suggests, “Kind of fits the definition of ‘objects of history and scientific interest’” in reference to language of the Antiquities Act. Hadenfeldt laughs, “If this place doesn’t deserve to qualify as antiquities then pretty much no place should qualify. This is the living embodiment of the Antiquities Act. What people don’t understand is that as far as cultural resources go this is the big enchilada.”

Very true, as Regina Lopez-Whiteskunk says, describing Bears Ears as “a return of the Antiquities Act to its original purpose.” On top of that, Gessner realizes that the Bears Ears National Monument declaration is something new. “For the first time here was a confluence of Indigenous ideals of respect and worship for land, of the land’s holiness with the better motives behind America’s ‘best idea,’ the ideals that guided the creation of our national parks and monuments.”

Bears Ears National Monument was the project of the Bears Ears Intertribal Coalition. While he wants to “extend historical empathy” to Teddy Roosevelt but also “see him clearly,” he has to admit that Roosevelt “was a leader of a country that, touting its national virtues, broke promise after promise to Native people, driving them onto smaller and smaller parcels of land.” He continues, “The slaughter and extirpation of North America’s Indigenous population is our original sin, our sin of origin. Anyone who cares to think deeply about the idea of America must contend with it, stare it in the face. We killed those who were here. Not just the animals, but the human beings.” In his reduction of Bears Ears National Monument Trump has added to the long history of America’s treatment of its Indigenous people.

Restoration of Bears Ears National Monument, and extension of its management to the coalition, might be a small measure of atonement, a small measure of justice. It would serve the tribes by offering some protection for the Indigenous people who consider it sacred, while at the same time serving other Americans in other ways. “I am convinced that places like this are exactly what our battered, shallow, exhausted, cynical country needs right now, Gessner writes. “A place to be reborn, a place to get outside of oneself and one’s tired time, a place to make us seem less central to our own story, a place to maybe even feel something like hope.” Restoring the monument would serve the interests of the Coalition tribes and at the same time those of the greater American community.

Gessner concludes his travels with a visit to the annual Bears Ears Summer Gathering in a meadow below the eastern lobe of Bears Ears. He interviews Regina Lopez Whiteskunk, who makes this very argument, pointing out that in the Bears Ears campaign the tribes requested a tool, government designation, that has always been used against them, for a decision in their interest, but also in the broader American interest. They joined with environmental groups and the federal government in this campaign, against provincial interests of Utah politicians. Gessner quotes Lopez-Whiteskunk,

“Seeing Bears Ears reduced by eighty-five percent, to two small pieces of land, leaves us with a memory that we’ve already gone through,” Regina continued. “The only difference about this time is it’s not my people specifically, the Ute Mountain Ute or any one tribe, that feel that reduction in the pain of feeling like something was taken, but it’s the American people. The American people now, as a whole, because it was a public land area, we all feel the pain of having something taken away from us. And so now, it’s not just a tribal people. It’s all the United States citizens whom all public lands belong to. We all have a share in that. And so the pain is shared.”

A powerful statement in a powerful book. Lopez-Whiteskunk speaks of what Gessner calls “confluence,” Indigenous people and others working together to save a rich and sacred piece of public land, and being rudely slapped down, something the tribes know well, but the rest of us perhaps not so much.

Leave it as It Is is the most engaging and powerful book about Western public lands that I have read in a long time. Gessner published a terrific book in 2015 titled All the Wild That Remains: Edward Abbey, Wallace Stegner, and the American West, and I find some Abbey and Stegner in this new book, both in style and content. He traveled the West in search of Abbey and Stegner in that book as he does with Teddy Roosevelt in this one. He looks at all these icons in the context of the modern West with a clear and analytical eye.

What I get from these books is a deeper understanding of what is at stake in the public land “wars” of today and of how and why those of us who love Western landscapes and their people, especially the Indigenous people who we have so egregiously wronged, must act. If you are not already in the fight for public lands and especially for Bears Ears, read this book and you will be inspired to get to work.

Comments

It is a good book, actually a very good book, tragic in many ways, but a tragedy we need to stand up and face.

"Leave it alone. You cannot improve on it." Can you imagine an American president making that statement in 2020? Maybe in a couple of months...

Let's hope so!