Caribou crossing the Kobuk River/NPS, Kyle Joly

It is a spectacle of the animal kingdom, one most of us don't see in person, but are amazed when it is shown on television. "It" is the crossing of the Kobuk River far north in Alaska by hundreds of caribou. It is a swim caribou have been making in the landscape of present-day Kobuk Valley National Park and Preserve for thousands of years.

“I’m a very lucky person to have the job that I do and to see what I get to see," admits Kyle Joly, a wildlife biologist for the National Park Service whose "office" embraces the landscapes of such places as Kobuk Valley, Gates of the Arctic National Park and Preserve, and Noatak National Preserve.

Kobuk Valley has been "the home of caribou migrations for 10,000 years. There’s an archaeological site there that’s dated hunting of caribou back that far," Joly went on. "The river is probably a quarter-mile wide at that point, and there will be times when you have several hundred animals on the shore. You’ll have caribou nose-to-tail all the way across the river, and a couple hundred more piled up on the south bank. It’s definitely a wildlife spectacle that is on par with anything on the globe.”

That spectacle, of hundreds and even thousands of caribou traveling en masse, is a wonder of nature. It is also at times the longest migration on Earth, a claim that reindeer also can make.

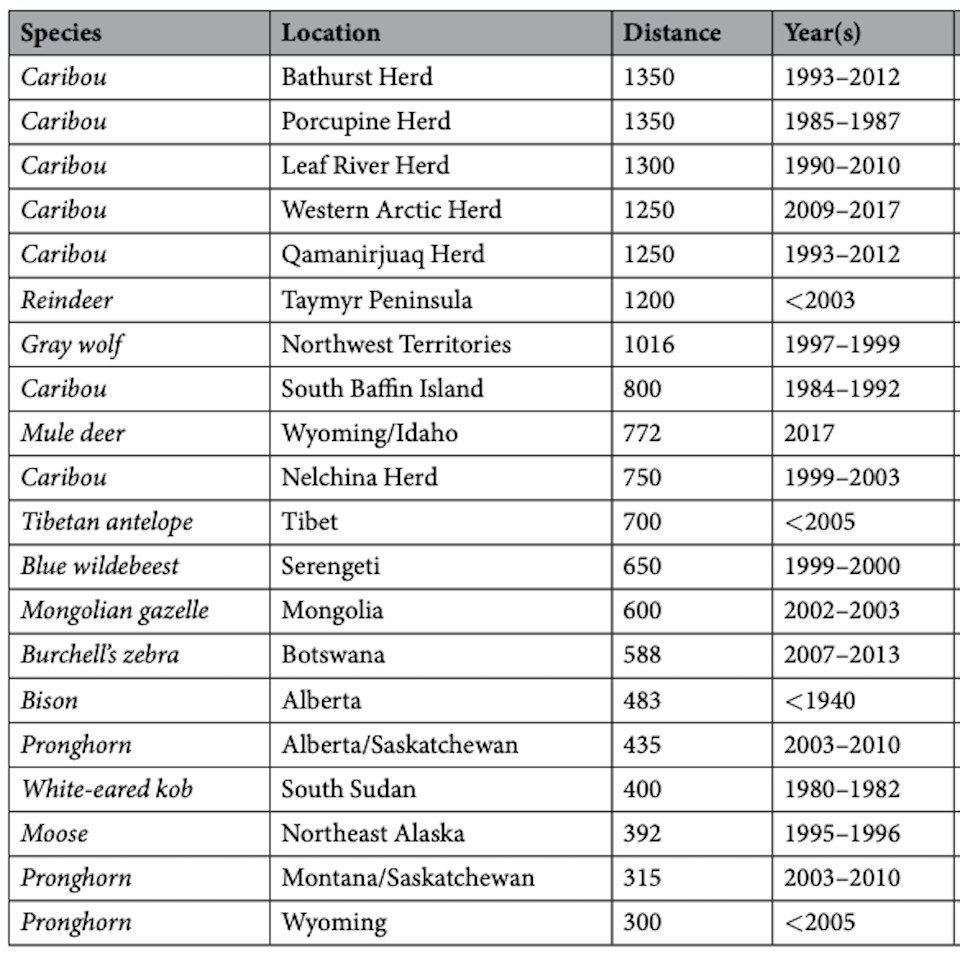

“Most people don’t know this, but caribou and reindeer are actually the same species," Joly said. "Caribou are found in North America and reindeer are found in Europe and Asia, but they’re the same species and they can interbreed freely. That species, both caribou and reindeer, have the longest terrestrial migrations on the planet, with a number of populations migrating 1200-1350 kilometers (745-839 miles) in a year.”

Wildlife migrate for a variety of reasons, though one that resonates most with us is their ever-present search for food.

"One of the classic reasons is to get food, and so in a lot of places that have high seasonality, where you have short, brief, summers and long, cold winters, animals will migrate to those areas where there’s a lot of high vegetative activity in the summertime," explained Joly, who earlier this fall published a paper detailing the migratory habits of caribou. "You’ll see that with birds, you’ll also see that with caribou.”

The biologist's research into terrestrial migrations around the globe found that caribou -- with one interesting exception -- were the only species that traveled more than 1,000 kilometers, or 621 miles, in their migrations from wintering to summering grounds. The other species was a pack of gray wolves, but more on that later. The roundtrip distance, for both species, usually comes down to nourishment, according to Joly.

"A lot of the animals will migrate in a generally north direction to have their calves, and the calving is timed with the flush of new nutritious growth. Oftentimes it’s tussock tundra. It’s a grass species that has a lot of protein, which is very important for females who are nursing newborn calves," he explained.

Interestingly, the Western Arctic caribou herd in recent years hasn't found the urge to travel so far so often, something Joly thinks might be related to climate change.

"It’s the largest caribou herd in the country and one of the largest in the continent and on the planet. The last couple of years has actually seen less and less animals migrate," he said. "We’re not exactly sure why that is, but one hypothesis is that the animals are benefitting from a longer growing season due to climate change, and so they’re actually getting in better condition and don’t feel the need to migrate as much.

“In the typical year," he went on, "we probably saw maybe 15 percent of animals not migrate in the traditional manner south to their wintering grounds. So that was pretty common, about that many, about 15 percent. Two years ago, we had about 50 percent of the animals not migrate, and last year we had about 80 percent of the animals not migrate. Quite a bit of change.”

Whether continued warming of the planet could cause the herd one day to lose its migrational instincts remains to be seen.

"One thing when you study caribou is you’ll note that there’s just an extreme amount of variation from year to year, what the herd does but also what individuals do," said Joly. "So at this point, I don’t think that we’re in danger of losing that migration. But thinking out 20, 30, 40, 50 years, those things need to be seriously considered in the face of climate change, in the face of just a slew of development proposals in the region.”

Wolves may or may not migrate, but they can travel vast distances/NPS, Kyle Joly

During his research, Joly came across a 2001 study that looked at a pack of gray wolves in the Canadian arctic of the Northwest Territories.

"They would give birth at their dens, and then in the winter they would chase caribou herds around. And so (the researchers) classified them as migratory," the Park Service biologist said. “I think that opens up a lot of questions on how to define migration. Maybe that’s a different topic.”

In the Lower 48, or coterminous states, there are wolves that travel great distances. Back in the fall of 2014 a wolf from near Yellowstone National Park traveled at least 450 miles to the North Rim of Grand Canyon National Park, according to the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. But that was believed to be the case of an individual wolf dispersing in search of a new mate and a new territory, not a migrational movement.

“In Alaska we do have packs that den in a certain spot and then follow caribou around. Maybe to the southeast, it maybe to the southwest, it could be any direction, and then they’ll come back to their den," Joly said. "Most people think of migration as discreet movements from one seasonal area to another seasonal area. For caribou, generally that’s a calving area in what we call spring. But often in the north it’s the first week of June, and then they’ll generally trend south and find a place to overwinter and then they’ll come back to their calving area, and that’s their migration.

"If you think of it similarly for wolves, they’re at that same den site, and they have even more fidelity than caribou," he continued. "Caribou calve in a calving grounds, but that specific location can bounce around from year to year. Wolves very often will den in the exact same den site, so they actually can have higher fidelity to their birthing area, and then the caribou will winter in different areas from year to year. The wolves, where they’re spending their winters if they’re chasing caribou will depend on where the caribou are, so they have about the same amount of fidelity to their wintering area.

“It gets complicated, but there is an argument to make that some wolves are migratory, depending on your definition.”

Migrations are critical for some species, as they need to find ample food for their numbers, or calving grounds large enough to accommodate the pregnant cows. Development -- highways, railroad corridors, the sprawl of communities -- all can put these seasonal movements in jeopardy. There are efforts to ensure continued connectivity, whether it's the Yellowstone to Yukon initiative or the work by the Wildlands Network to link public lands in the United States. But migrations can be complicated, points out Joly, as not all involve a north-south trajectory. Some could simply being moving from higher elevations to lower elevations, as bison in Yellowstone do from summer to winter.

“One thing that is very admirable about the (Yellowstone to Yukon) project is that it’s looking for habitat connectivity. That’s one of the major influences on loss of biodiversity and loss of migrations is loss of large intact ecosystems," the biologist said. “Certainly, we’ve seen more attention (to the problem by other groups). I think the Yukon to Yellowstone initiative has kind of taken it to the next level. It’s a much bigger scale project. I think we’ve seen it at smaller scales. You can look at it at the very fine scale: We’ve put in underpasses and overpasses for a variety of wildlife species to connect habitat so that they don’t get run over as they’re crossing highways and things like that. It’s just a matter of scale. The same goal of connecting those habitats so wildlife can roam freely.”

As climate change continues to develop, preserving corridors for faunal movements will only become more important, said Joly.

In tracking migratory species, Joly came up with a list of the longest recorded migrations. Caribou claimed the top five spots (the Bathurst, Porcupine, Leaf River, Western Arctic, and Qamanirjuag herds), followed by reindeer (the Taymyr Peninsula herd), gray wolves (Northwest Territories), another caribou herd (South Baffin Island), a mule deer herd (Wyoming/Idaho), and yet another caribou herd (Nelchina herd).

Maximum Euclidean (straight-line), round-trip distance (RTD, in km) for different long-distance, terrestrial mammalian migrations/Kyle Joly

Traveler footnote: Listen to the full interview with Kyle Joly in National Parks Traveler Episode 43: Longest Terrestrial Migrations, And Jean LaFitte National Historical Park.

Add comment