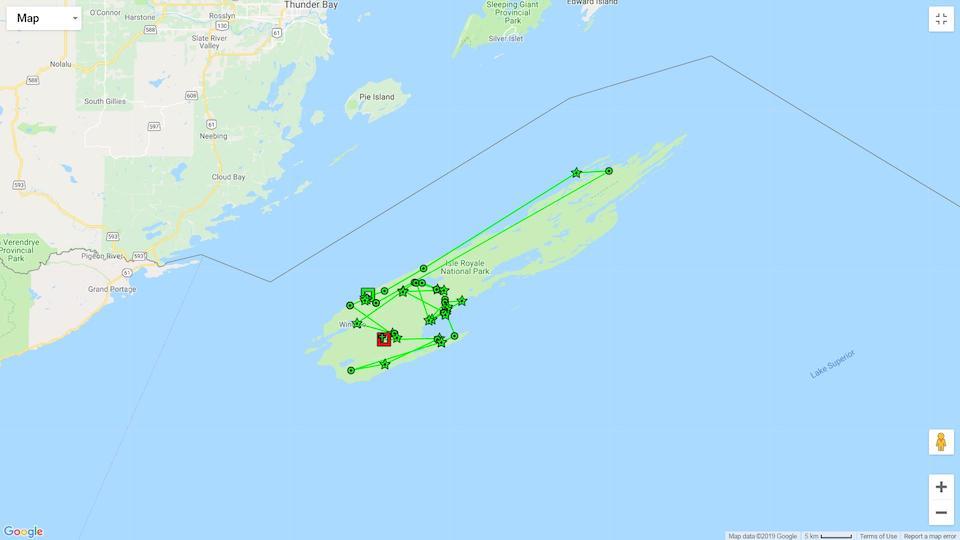

Locations of W006M from late February through early April, when its collar stopped transmitting.The red box on the map is where the wolf was found/NPS

A wolf transported to Isle Royale National Park from Canada in late February as part of a recovery effort to balance prey and predators at the park has turned up dead. Unfortunately, its carcass was too badly decomposed by the time it was recovered for a determination of what caused its death, park staff said Wednesday.

The loss lowered the island's wolf population to 14. Since the National Park Service last year decided to move ahead with a wolf recovery program at Isle Royale, a dozen wolves had been moved to the island in Lake Superior from Canada and Minnesota to join two aging members of the park's last remaining wolf pack. One wolf died of pneumonia shortly after being released at Isle Royale, and another left the island via an ice bridge that was in place for a short time early this year.

Park staff were alerted to the latest loss in late March, when they detected a wolf’s GPS collar transmitting a mortality mode signal. The wolf (W006M) was a black-coated male translocated to the park from Ontario, Canada, in late February. Park Service personnel, unable to access the island at the time, had to wait until the park reopened for the 2019 season to investigate.

According to a park release, the "wolf was located in the middle of Siskiwit swamp, a large wetland complex at the southwest end of the island. NPS personnel and cooperating investigators from State University of New York-College of Environmental Science and Forestry (SUNY-ESF) using coordinates provided by the GPS collar traveled five miles into the swamp to recover the carcass and determine the cause of death. The GPS collar quit transmitting two weeks prior. Investigators found no apparent signs of injury or struggle, however, the carcass was in a very deteriorated state due to melting snow and wet conditions, making an accurate cause of death determination impossible."

The park release stated that the survival rate of wolves in the nearby Upper Peninsula of Michigan is approximately 75 percent; conversely, approximately 25 percent annual mortality can be expected.

“After translocation of 11 wolves this winter it was a disappointment to learn of this mortality and even more frustrating that the carcass could not be accessed in a timely way for a detailed necropsy,” said Mark Romanski, Isle Royale's division chief of natural resources. “A few weeks prior, this male was traveling with one of the females translocated from Minnesota in October 2018. It would have been nice to see them stay together.”

By monitoring GPS data biologists believe the new wolves are beginning to form loose associations. "A female wolf (W001F) translocated from Minnesota in September of 2018 and two male wolves ( W007M and W013M) moved from Michipicoten Island, Ontario, Canada, this winter have been traveling together since early April," the park release noted.

“While GPS data indicate these three wolves have been together on numerous occasions, it’s too early to tell whether we have a makings of a wolf pack,” said Romanski. “But it is reassuring that we have wolves spending time together and feeding.”

The Park Service and partners from SUNY-ESF have initiated a study to look at summer predation and are using GPS locations to determine “clusters”, a group of consecutive GPS locations within 50 m (55 yds) of one another, for investigation as to whether wolves have made a kill, are scavenging, or perhaps just resting. This data will help managers and scientists determine the impact the wolf population has on the island’s moose population and document predation of other species such as beaver and snowshoe hare. Less commonly discovered is the predation of snowshoe hare. Akin to finding a needle in a haystack, searching two clusters each an area of nearly 0.8 hectares (two acres) field technicians discovered two probable snowshoe hare predation sites this past week; often all that remains at these sites are the feet, which wolves typically do not consume.

Isle Royale wolves have been in decline for more than a decade, due to chronic inbreeding. There was hope that "ice bridges" that formed between the Lake Superior island and the Canadian mainland during the winter of 2013-14 would enable wolves to arrive from Canada with new genes. But no new wolves reached the island, while one female left and was killed by a gunshot wound in February 2014 near Grand Portage National Monument.

In recent years, park managers have discussed wolf management on 209-square-mile Isle Royale with wildlife managers and geneticists from across the United States and Canada, and have received input during public meetings and from Native American tribes of the area. Those discussions examined the question of whether wolves should be physically transported to Isle Royale, in large part due to concerns that a loss of the predators would lead to a boom in the moose population that likely would over-browse island vegetation.

Under the plan the National Park Service adopted last year year, up to 30 wolves are to be set free at Isle Royale over the next three years in a bid to build genetic diversity into the park's wolf packs. In late February, the Ontario Ministry of Natural Resources and Forestry successfully transferred four wolves to Isle Royale.

Listen to one of the wolf researchers discuss the recovery plan with Traveler's Erika Zambello on a recent podcast.

Add comment