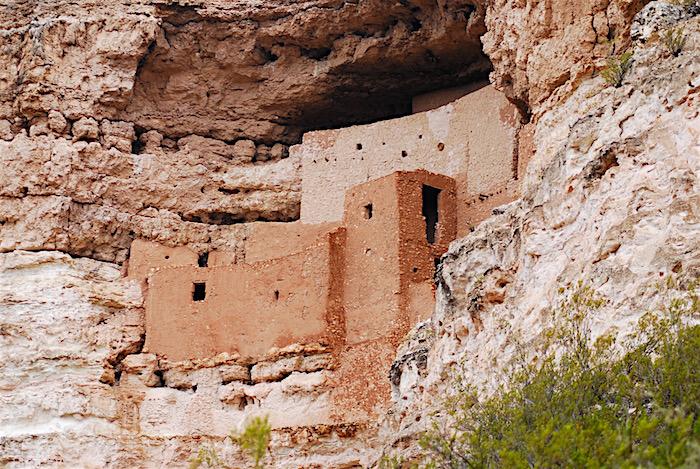

Montezuma Castle in Arizona is the hallmark of a long lost civilization/Kurt Repanshek file

In the center of Arizona lies the fertile Verde River Valley, one of the longest free-flowing rivers left in the state. This area has long supported human habitation, and the remnants of these ancient cultures are protected and preserved at Tuzigoot and Montezuma Castle national monuments. I was recently there to learn about these early residents and score a couple more stamps in my national parks Passport.

The original inhabitants were hunters and gatherers who thrived in the rich environment supported by the year-around river. The first permanent structures in the valley appeared between 700 and 900 CE (Common Era). The Southern Sinagua people started building the region’s large pueblos in about 1000 CE, and it is the remnants of one of those hilltop pueblos that drew us to Cottonwood, Arizona, just three short miles away from Tuzigoot. Tuzigoot is the largest and best-preserved of these Sinagua Pueblo structures in the whole of the Verde Valley.

I was traveling with my sister Sandy and my girlfriend Craig, and after a good night’s rest at the Cottonwood Hotel in Cottonwood’s historic district we found ourselves birding in the Verde River Greenway State Natural Area, a 6-mile stretch of especially rich riparian habitat set aside between the towns of Clarkdale and Cottonwood by Arizona State Parks, and easily accessed on the short drive to Tuzigoot. It is easy to imagine the entirety of the river supporting this rich habitat, and this habitat, along with the agriculture made possible by the river, supporting a large indigenous population.

Interestingly enough, it was not the river’s agricultural potential that drew large numbers of non-native peoples to the region. It was copper. The population in the valley took a big jump in the early 1900s with the growth of copper mining and smelting. Cottonwood grew from the copper boom, but it was not a company town, unlike neighboring Clarkdale and Jerome, and that independent vibe still exists today.

Verde River Valley from Tuzigoot/Jim Stratton

When the first round of mine closures hit in the 1930s, it was University of Arizona archaeologists’ desire to protect and preserve Tuzigoot that provided employment for out-of-work miners and other area residents. The Civil Works Administration and later the Works Project Administration, working closely with the University of Arizona, excavated the site using this local labor. The site was originally owned by Phelps Dodge Corporation, but they sold it to Yavapai County for $1 so the excavation work could be done under federal work project programs. President Franklin Roosevelt designated Tuzigoot as a national monument in 1939.

The workers in the 1930s developed what is now a well-worn path from the charmingly rustic visitor center through the pueblo ruins to the top of the hill 120 feet above the floodplain. At the top you have a wonderful 360-degree view of the Verde River Valley. The ruins are mainly waist-high walls of rock showing you the 100 or so rooms that have been reclaimed. The trail is well interpreted, giving visitors an idea of what the rooms were used for. The visitor center not only has some huge water pots recovered during the archaeological excavations, but it tells the story of the archaeological work done in the 1930s under the WPA. Most of the pots are reconstructed from hundreds of pot shards painstakingly fit together like a Jigsaw puzzle by WPA workers 80 years ago. I marveled at the patience it must have taken to sort through piles of pottery chips to rebuild these pots. Just north of the visitor center, a trail leads you to overlook a wetland that is a focus of the twice monthly birding walks (second and fourth Saturdays) offered by park staff during the winter.

View from the visitor center at Tuzigoot/Jim Stratton

It doesn’t take long to visit Tuzigoot, and after a filling breakfast of huevos rancheros back in Cottonwood at the Red Rooster Café, and a walk down main street to check out its diversity of shops and wine tasting rooms, we were on our way to Montezuma Castle, about a half hour away. Located just off Interstate 17 about 50 miles south of Flagstaff, Montezuma Castle was a bustling site with a full parking lot of visitors on hand to see the Sinagua Pueblo built into the side of the limestone cliff. Too bad I hadn’t been able to visit in the 1960s when you could still climb the ladders into the pueblo and explore it first-hand. You are now limited to a view from the trail. A small-scale model built by the Park Service gives you an idea of what it must have been like with people living there. The Castle is about 20 rooms, and is estimated to have housed about 35 people. There is observable evidence of additional housing built into the cliff, making this one of about 40 large villages identified throughout the valley. President Theodore Roosevelt created the monument in 1906 in one of the earliest uses of the Antiquities Act.

But the really cool site at Montezuma Castle is not the Castle. It is Montezuma Well, a short 11-mile drive to the north. The well is a naturally occurring sinkhole filled with 15 million gallons of water. Local Native American people consider this a sacred site and a place of origin. Think of the well as a limestone bowl 130 yards across and filled about halfway. You stand on the rim of the bowl and look down into the small lake that is the well. I have seen other limestone sinkholes, but one filled with so much water is not a sight one expects in the desert. From the parking lot it is about a third of a mile up to and around most of the well.

Montezuma Well, with cliff dwellings/Patrick Cone

As we peaked over the rim for the first time, we were greeted not only by this huge body of water, but also by ducks – buffleheads, northern shovelers and American widgeons. We wondered what they ate besides the vegetation that grew along the water’s edge. Are there any fish in the well? Fortunately there was no shortage of interpretive signs and we quickly learned that with a carbon dioxide level 80 times greater than most lakes there are no fish. But there is a unique ecosystem that includes small shrimp-like amphipods, a specialized species of snail and thousands of leeches, all food for birds.

For those a bit more adventuresome, there is a short trail down to the water’s edge, and I didn’t hesitate to scramble down to check out the lake at water level. There are two springs at the bottom of the well that provide about 1.6 million gallons of water daily, even in times of drought. So about 10 percent of the water turns over each day. The trail leads to an outlet that flows 150 feet through the travertine limestone wall and into Wet Beaver Creek on the outside of the well.

There are cliff dwellings inside the well, including several built into caves near the outlet. Jerry, a very nice park volunteer, told me about the graffiti in these caves – not ancient paintings, but more recent scrawlings including an advertisement for George Rothrock Photography dated 1878. It seems that for a short time George claimed “ownership” of the well and charged people to take their photos along the edge of the lake.

Exploration of these caves is not permitted for obvious reasons. They are small, narrow, and could easily be destroyed by too many well-meaning visitors. But Jerry told me that locals who had explored the cave before they were closed off reported that Samuel Clements (Mark Twain) visited the site and wrote his name inside the cave, alongside notations from other 19th century visitors. I liked that I was standing where Mark Twain might have once stood.

Rothrock Photography, Montezuma Well/Jim Stratton

Back up on the rim, the trail takes you down the outside of the well to where the outlet hits Wet Beaver Creek. And there we discovered remnants of a 7 mile canal that linked the well and its perpetual water supply with the agriculture fields near Montezuma’s Castle. Seems the canal wasn’t needed every year, only when the rains didn’t come. But in those times of drought, these Verde River Valley residents had a steady supply of water to feed their crops of cotton, squash, beans and agave. The Park Service is currently restoring the canal.

We’d been told by several people we met in Cottonwood that the Well was not to be missed. How right they were. This is a hidden gem in the desert and now one of our favorite places.

The Outlet creek from Montezuma Well/Patrick Cone

Comments

Article says nothing about the inhabitants being farmers. Missed the whole farm land and irrigation system they engineered