Editor’s note: The following is a release from the National Park Service’s National Resource Stewardship and Science Directorate.

A new, first-of-its-kind study shows the National Park Service is home to a whopping 53 unique species of bats, which is good news at a time when bats face tremendous threats. For the past decade, park staff and researchers have witnessed unprecedented declines in bat populations, spurring the need for a comprehensive review of bat species and habitats. The study highlights the high diversity of bats in the NPS as well as the need for more strategic conservation measures.

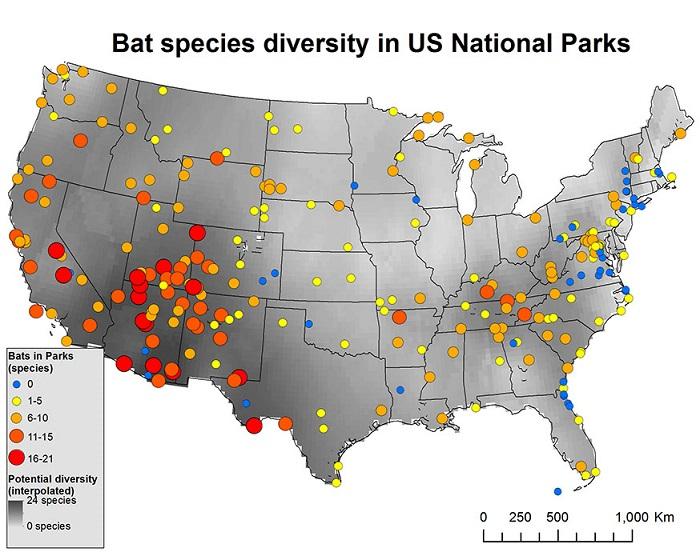

“This is the first time we’ve had a complete view of all the bats in parks across the country. It’s really exciting because we have so many bats to celebrate – including as many as 21 species in Big Bend National Park – but it’s also sobering because of the huge responsibility we have to try and keep all those bats in parks safe,” said Tom Rodhouse, NPS ecologist and lead author of the paper.

Townsend's big-eared bat is one of 14 species at Lava Beds National Monument in California/NPS, Zach Kaiser

For this study, Rodhouse combed through park bat records in NPSpecies, the service-wide database of all species’ status and occurrences, and compared those records to species range maps. He also studied how the spread of the bat disease white-nose syndrome (WNS), wind energy development, and climate change will affect bats in parks.

Published this month in Ecosphere, the paper “A macroecological perspective on strategic bat conservation in the US National Park Service” provides a comprehensive review of the many species of bats in parks and also of the important bat resources, like caves and abandoned mines, as well as the existential threats facing bats in parks.

The analysis uncovers gaps in data – places where certain species of bats are possible in a particular area but haven’t yet been documented. Equipped with this information, park biologists can focus their efforts in these areas and develop a more complete inventory of the species of bats and habitats used by bats in national parks. This approach offers opportunities for bat conservation in any park – not just the so-called “bat parks,” known for their large caves.

“I discovered that literally hundreds of parks are all dealing with the same challenges. For example, 10 years ago we thought widespread species like the little brown bat and the hoary bat were fine,” Rodhouse said. “Now, they’re suddenly facing extinction because of white-nose syndrome and wind turbine collisions.”

It’s crucial for park staff and researchers to know where bats live, hibernate, and migrate in order to protect them. Bats face many significant threats that are decimating bat populations all over the U.S. Wind turbines endanger migratory, tree-roosting bats; WNS, a fungal disease that affects hibernating, cave-dwelling bats has killed millions of bats since 2006; habitat loss, like deforestation or fragmentation, affects many species of bats; and climate change is a challenge for all bats because they are so sensitive to changes in temperature and water availability.

WNS is one of the most dangerous threats at this point. This summer, a bat sick with WNS was found in Washington near Mount Rainier National Park. This discovery far out-paced predictions of WNS’ spread, and it further underscores the need for large-scale studies of bat populations and movements to better understand impacts of the disease and pathways of spread.

Threats to bats don’t respect boundaries, crossing from federal to state to private lands and often disrupting migratory paths. Bats themselves are also so wide ranging that bat conservation efforts will be most effective when done collaboratively across broad regions using similar methods. Parks can serve as places for study but will need to be part of larger partnerships in order to have the context to really understand how their bat populations are faring. This study helps the NPS make strategic investments in bat conservation and provides a baseline of bat diversity that can be used for future comparisons.

Visit nps.gov/bats to see this map that shows how many species of bats have been confirmed in individual parks, as well as parks that possibly contain bats that haven’t been documented. You’ll also find a complete list of bat species in national parks.

Read the full paper by Rodhouse et al. published on November 9, 2016.

Comments

"I discovered that literally hundreds of parks are all dealing with the same challenges. For example, 10 years ago we thought widespread species like the little brown bat and the hoary bat were fine," Rodhouse said. "Now, they're suddenly facing extinction because of white-nose syndrome and wind turbine collisions."

Wind turbine collisions, is it? But I thought wind power was green. At least, that is what the liberals here in California have been telling me. Not to worry. We have the extinction problem under control. The Zika virus? West Nile virus? Who will now be killing the mosquitos that carry them? Don't tell me! Governor Brown!

Atescadero--

Wind turbines aren't all the same. There are several things that can be done to minimize the impacts of wind turbines on bats (& birds), starting with where they are sited, but including heights & rotational speeds and making them more "visible" to the sonar, or not running them at peak migration times. Such modifications often slightly reduce the engineering-potential power production, increasing the costs and decreasing the profits. Different bat species fly at different heights and forage in different areas, so some modifications only help a subset of bat species. Some modifications that reduce potential harm to bats increase potential harm to birds. Like most engineering, there are tradeoffs, and better empirical information allows design to minimize the negative impacts at the smallest cost to the positive output. One point of this bat work is to understand where different species of bats are, to help site wind turbines where bats aren't, and to help argue for types of wind turbines that affect bats less in specific areas of higher potential impact to bats.

[Dealing with wind turbines is the domain of FWS and USGS; NPS is more directly involved with slowing the spread of white-nose syndrome via visitation to its caves. This paper grew out of parks' needs to understand which species of bats they have, both for resource monitoring and for resource management, but the results are useful to other agencies and tribes. There is an inter-agency task force for bats to coordinate work, reducing duplication of effort (saving $$, or really just getting more bang for the buck with the limited $$ available for such issues), and supporting better understanding of bats moving across land management boundaries.]

I'm biased: I'm second Tom author of that paper, and I'm a liberal here in California. However, I assert that my views are more influenced by my science and engineering background than my politics.

Yes, we human beings are so convinved we can "mitigate" the worst of our foibles and excesses. But what if we can't? What if, no matter what we do, wind turbines contribute to the destruction of life? Which they do, which leaves us to shout "mitigation!", because the excesses are what we want.

Aldo Leopold said it best: It's not the land that is sick; it is rather that we are sick, and here is another prime example. We create the sicknesses in the first place, as if mitigation is in fact something positive. It's not positive in the least. It's just another piece of word magic--now meant to shove us in the wrong direction before we dare ask what is really happening. Would we ordinarily kill off everything else on this planet that needs to fly, crawl, or swim? In the old days we dared call that unethical. Now we call it mitigation, i.e., "engineering" requiring "tradeoffs" so we may "minimize" our excesses. Jerry Brown, our state's original sellout, calls himself a "liberal," too. Pardon me, but I have a different name for a governor who thinks himself better than the rest of us for being "liberal."

This sounds like a good study that I should read. This is the type of work that needs to be done to manage the national parks overall and help out the bats. More information is always better than less when you are making decisions.

Dutch researchers have detected a cocktail of 14 different pesticides (fungicides, herbicides, insecticides) in bats. In dead individuals and manure classical insecticides such as DDT and permethrin were found, but the animals were also exposed to the neonicotinoids imidacloprid and thiamethoxam, the herbicides mecoprop and nicosulfuron, and the fungicides iprodione and propiconazole. Pesticides such as imidacloprid, propoxur, thiamethoxam, nicosulfuron and iprodione had not previously been reported to be present in bats. The observed concentrations may not be acutely lethal to bats, but chronic effects including immune suppression, which would explain the endemic white nose syndrome that killed millions of bats in North America, can not be ruled out.