There are those for whom forts of any kind do not a national park experience make.

For them perhaps, a new unit of the park system, Fort Monroe, Virginia, is now a national monument'the largest stone and masonry fort in the United States, no less. There are dozens of smaller such forts strewn around our coasts in national parks, seashores, lakeshores, state parks'erected in separate waves of 1800s effort to defend the early United States.

This fort, however, embodies much more than just a historical look back at the 'coastal fort era.' Militarily, Fort Monroe reaches back to the 17th century and moves from there forward to the 21st century'as in last year.

On this same site was the very first defensive embrasure erected by English settlers in the New World. This is such a perfectly strategic site that the folks at Jamestown sailed over to fortify it in 1609. Fort Monroe was also an active Army base from 1819 until 2011, which makes it the longest serving military installation in our history. More than that, the range of military technology arrayed at this fort traces the active defenses of the United States back from way before the Civil War to well after WW II'a pretty broad span of relevance.

And that's the 'boring stuff,' albeit, a list of distinctions that delivers a glimmer of just how pivotal this place is. All of the above and more is why the surrounding, heavily military and tourism dependent communities of Hampton, Newport News, Norfolk, Portsmouth, and Virginia Beach, are talking about the future of this new 325-acre national monument. More accurately, the talk is largely centered on the equally historic 240 undesignated acres of the former base that could be privatized and developed with unknown impacts on this jewel in the rough.

Jamestown's Fortress

No one living today can imagine the overpowering wilderness surrounding 17th century Jamestown. Factor in Indians, the Spanish and Dutch, and it's easy to understand why settlers under John Ratcliffe came back to Old Point Comfort to build Fort Algernourne (or Algernon) in 1609. The site oversees the entire entrance to Chesapeake Bay, one of the largest harbors in the world. It also dominates the James River channel to Jamestown'so it was perfect as a first line of defense for the colony.

John Smith had chosen the site and unknowingly foretold the future by calling it 'a little isle fit for a castle.'

By 1614, that early fort was a stockade that housed 50 people and seven cannons. The fort didn't defuse friction with the Indians. In 1610, the colonists 'expropriated' a fertile farming area from the local Kecoughtan Indians, starting an era of bad blood that killed a quarter of the colonists in a 1622 Indian assault. The fort burned to the ground in 1612, was rebuilt, and then rebuilt again in 1632 as Old Point Comfort Fort. It was discontinued in 1667 and twice within the folowing six years Dutch warships burned English vessels near Jamestown.

The Algernon Oak, between 400 and 500 years old. Fort Monroe is reputed to be the northernmost limit of the live oak species. US Government photo.

Another fortified site came to Old Point Comfort in 1727'Fort George'a formidable defense with masonry walls separated by 16 feet of sand. But that entire structure washed away in a 1749 hurricane leaving the point empty till Fort Monroe rose 70 years later.

During the American Revolution, Lord Cornwallis thought the point was 'poorly situated for defense,' so he landed at Yorktown'where he was surrounded and soon surrendered.

Today, as you wander among the gnarled live-oaks that dot the 63 acres enclosed by the monumental walls and moat of Fort Monroe, be sure to stand beneath the rustling leaves of the Algernourne Oak. At 500 years old, it was very likely growing when the blunderbuss was being carried by troops here in the early 1600s.

It was also growing when the battle between the USS Monitor and the CSS Virginia echoed offshore, ending the age of wooden warships. And it still grows as nuclear subs sail by'albeit with cables supporting its massive limbs.

Phases of Construction

In 1794, a 'First System' of forts was launched in the young United States. Among those was Baltimore's Fort McHenry that survived British bombardment in the War of 1812. Another phase of forts was started that completed more than 60 forts and batteries by the start of the war.

Robert E. Lee's quarters like other residential structures are now private rental residences. Randy Johnson photo.

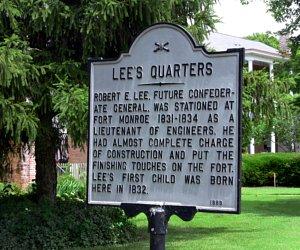

The current fort got its start in 1817 after the War of 1812. The U.S. Senate resolved to survey the entire maritime defenses of the country and build a comprehensive system of forts. 'Fortress Monroe' took 15 years to build, starting in 1819. Robert E. Lee was an assistant engineer at the fort from 1831 to 1834, and oversaw major projects including work on the ramparts, completion of the moat and water battery (away from the main walls, on the water's edge, that was mostly removed in 1907).

Lee was among those most promising early graduates of the fledgling U.S. Military Academy who were usually assigned to the Army's prestigious Corps of Engineers. Lee's wife joined him during his assignment, and they had their first child at the fort.

While a resident engineer in the early 1830s, Lee put the final touches on the moat. Visitors are permitted to walk the grassy tops of the walls around the entire fort'but be careful! Randy Johnson photo.

Lee's quarters are just across the street from the fort's great Casemate Museum (see this article for a tour of the museum and fort). The museum occupies a number of casemates'defined as, 'A vaulted, bombproof room of masonry construction used as a firing position for a cannon.' (Check out the Museum's Facebook page.)

Lee also worked on what's now called Fort Wool, a flag-flying smaller fortress not far offshore from Fort Monroe that's a Hampton city park. That, too, has a fascinating history. It was the Presidential retreat of Andrew Jackson and John Tyler, and served as a prison camp during the Civil War. Late in the 19th century, the Army briefly detained chief Black Hawk on the manmade island.

Freedom's Fortress

The rich military history of the fort actually includes a pivotal incident in the cultural history of the United States.

In 1861, three escaped slaves owned by Confederate Colonel Charles Mallory sought refuge in the fort.

When the Confederates demanded the runaways be returned under the Fugitive Slave Act, Fort Monroe's commander, Major General Benjamin F. Butler, refused to hand then back. Calling them 'contraband of war,' Butler's 'Fort Monroe Doctrine' set the stage for the later Emancipation Proclamation. It also precipitated a large settlement of former slaves who called their new home 'Freedom's Fortress.'

In the absolute peak of irony, Butler's decision was made on the same site where in 1619, the first Africans arrived in the British settled New World, effectively starting slavery.

Butler's action is one of the great stories of the war. He brought a new source of manpower into play for the Union, first for construction, then as combatants. Later in the war, the First and Second Regiments of U.S. Colored Cavalry and Battery B of U.S. Colored Light Artillery were raised from the refugee community surrounding the fort.

During the war, Fort Monroe was used as a base of operations for attacks at many locations along the coast and as a staging area for the 1862 Peninsula Campaign against Richmond. The fort was a military balloon camp for a time, and a flight there is credited with the first successful aerial gathering of military intelligence.

President Abraham Lincoln made a few trips to the fort, staying at one point in Quarters #1, the oldest structure inside the fort and still standing (though a bit disheveled, see photo at top). Built in 1819, it is also one of the nation's longest-serving structures with a military pedigree.

The massive "Lincoln Gun" overlooks the parade ground in the heart of the fort. Randy Johnson photo.

Not far away, sits the 'Lincoln Gun,' perched on a mount in the center of the fort. Cast in 1860, this is the first 15-Rodman cannon, named for Lincoln in 1862.

After the war, one of Fort Monroe's casemates was a prison cell for Confederate President Jefferson Davis during a two-year stay at the fort. (For more, see our story on visiting Fort Monroe.)

Fort Monroe: Active in Defense

Fort Monroe was a military base for 192 years, longer than any other installation in U.S. history. That status wasn't ceremonial, but based on an ongoing evolution of the fort's very real role in coastal protection.

It was home to the Army's Artillery School from 1824 to 1906 and then the base of the Coast Artillery School from 1907 to 1946. In 1917, the first submarine net in the United States was strung between Fort Monroe and Fort Wool.

During World War II, the fort was equipped with the latest coastal defense technology, from "3-inch rapid fire guns to 16-inch guns capable of firing a 2,000 pound projectile 25 miles. In addition, the Army controlled submarine barriers and underwater mine fields." In the 1970s, the Army moved its Training and Doctrine Command Division (which deals with attracting and training recruits) to the fort. It remained there until the base was closed September 15, 2011, under the Base Realignment and Closure Act of 2005.

The Future Looms

With Superintendent Kirsten Talken-Spaulding just appointed late last year, National Park Service management at Fort Monroe National Monument is transitioning through the 'usual' start-up procedures.

Wonderful beaches flank the Bay side of Fort Monroe and run north back into national monument acreage. Preservationists are concerned this undeveloped shoreline will become overly commercialized. US Government photo.

But only 325 acres of the 565-acre sandy isle off the coast of Hampton, Virginia, is national monument acreage.

In the 1838 deed, Virginia stipulated that if the 'United States should ever abandon the said lands and shoals,' it would revert to the state of Virginia. That reversion is under way, with the Fort Monroe Authority moving forward with plans to preserve and likely further develop the 240-acres of this seaside spit that are not national monument. The goal: historic preservation and commercial diversification of the area with a focus on environment sustainability and financial self-sufficiency.

Some locals fear that future, having wished President Obama had drawn a much bigger boundary around the national monument he created in 2011 with the use of the Antiquities Act. In fairness, until President Obama declared the national monument, there was doubt even that would happen.

The Citizens for a Fort Monroe National Park lobbied for park status at Fort Monroe'and recently won awards for that effort from the National Parks Conservation Association and the Civil War Trust. They urge that the two separate parcels of national monument property (the fort itself and the northern beach area) be connected and that less of the land surrounding the fort be open to redevelopment schemes.

For now, the area's extensive, paved waterside bike path, kid-friendly, enticing bayside beaches, and free saltwater fishing at Engineer's Pier, are drawing fans. Any visitor would do well to consider making Fort Monroe a multi-activity, daylong experience (see our story on visiting the fort).

Former military recreational amenities, including the pool, beach and restaurant of the Paradise Ocean Club, are soliciting for members. There's also the Bay Breeze Conference Center and restaurant offering event catering.

While the intensive public input and planning process for the private land part of the peninsula is under way'a process that promises to be lively'the new national monument is also starting its solicitation of public input for planning purposes.

All of that promises to draw a major surge of new visitors. Anyone touring the fort for the first time pretty readily realizes how special this area is and how carefully, and consensually, change should come. It's pretty rare when one of the nation's oldest and most pivotal military and cultural monuments gets a chance to hit the reset button on the future.

When those sites occupy a pristine, priceless piece of lightly developed coastline in a burgeoning urban area'the burden of balancing past and future is weighty, indeed.

Comments

Transferring all "monuments" to NPS jurisdiction would eliminate the confusion over which agency is in charge. Given inter-agency turf battles such a transfer is probably unlikely. Maybe all BLM monuments could be redesignated as national conservation areas.

By the way, the Fish and Wildlife Service, the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, and the National Trust for Historic Preservation also oversee some national monuments.

The Traveler is indebted to anyone who helps keep our articles—and headlines—accurate. The offending misinformation has ... vanished! Appreciate the correction, Darren and Mike.

In response to the comment above from SS1 about a map of the Wherry tract that conservationists want added to the National Monument—visit this page, scroll to the bottom, and the area is marked in red on the map at right.

It's not completely clear that 72 acres is the accurate number. The Norfolk Virginian-Pilot calls it 100. The point is that the entire bayfront is crucial to the sense of place at Fort Monroe. The omitted bayfront acreage is marked by red on the National Park Service map that four of us modified to summarize the situation during local political campaigning this spring. Our modified NPS map appears at http://www.fortmonroenationalpark.org/images/Please_unify_split_national... and is also on the Web site http://www.fortmonroenationalpark.org/ . The earlier version cited in a reply comment below is OK but is not clear about the development area that will remain whether or not Virginia's leaders follow through on their plain national civic stewardship duty, which is to get the split national monument fixed by having its huge, gaping omission of crucial land incorporated in a national monument/park. (More on all of this to come in a longer comment that I hope to submit this morning.) Thanks.

(I’ve been deeply involved in the Fort Monroe struggle since September 2005.)

This article opens by declaring, falsely, that “Fort Monroe, Virginia, is now a national monument.” But it’s not, as the article makes clear only after opening with this misinformation that has hobbled the national media's, and the nation's, understanding of the American cultural disaster now being cemented.

Part, but only part, of the problem is the word _fort_. The stone fortress constitutes only about 20% of Fort Monroe, almost all of which had been a national historic landmark for a half-century before the Army’s 2005 departure decision -- and every square inch of which contributes to the sense of place. As can be seen in a glance at the modified National Park Service map at http://fortmonroenationalpark.org/, the president -- either snookered by or complicit with overdevelopment-obsessed Virginia politicians of both parties -- left a gaping hundred-acre hole in the bifurcated national monument’s sense-of-place-defining Chesapeake Bay waterfront. Moreover, and also as shown, in every scenario the west side of Fort Monroe will remain part residential and part new development.

"American cultural disaster." Strong charge. But please consider: In a 2007 documentary, Robert Nieweg of the National Trust for Historic Preservation (NTHP) ranked Fort Monroe with Monticello. Imagine a hillside at Monticello, leading right up to Thomas Jefferson’s house. Imagine that hillside sacrificed -- along with the viewshed and the sense of place -- for purportedly "compatible" redevelopment. That's akin to what Virginia's leaders grimly intend for Fort Monroe. They operate with astonishing complicity from NTHP and other preservation organizations that so far have failed, in this matter, to live up to their very names. And they operate with an equally astonishing lack of Journalism 101 skepticism by press-release-believing newsfolk at the Washington Post and elsewhere.

Readers should know that the article we're discussing extends a discussion seen in a 2011 National Parks Traveler article (/2011/09/update-historic-fort-monroe-moves-rapidly-toward-national-park-status-questions-cloud-push-preservat8784) beneath which many serious, carefully considered online comments were appended to show the falseness of the happy-faced version of all that has happened since the Army’s 2005 departure decision. For more than five of the seven years since then, Virginia’s leaders did not “vigorously” -- as one commenter now wrongly asserts -- pursue creation of the present national monument. Until 2011, officials vigorously, and sometimes unethically, scotched discussion of national park options. Then they vigorously pursued the fake, split national monument that unskeptical journalists are now helping them to cement.

That earlier article’s first paragraph cited “a serious issue [that] remains unresolved and underpublicized. If too little of the former military installation is preserved, bayfront land near the historic fort itself will surely be developed in ways very harmful to the historic site's viewscape and sense of place.” That issue remains unresolved and underpublicized, thanks in part to what amounts to a Big Lie when presented by Virginia's leaders: the falsehood that Fort Monroe has been made a national monument. Their cynical bamboozling has worked. Not only has it fooled journalists, but weekly here in Virginia I run into someone who exclaims, "Well, Steve, I guess you're happy that all those years of effort paid off, and now Fort Monroe is a national monument!"

Another part of the problem stems from an unrecognized, unintentional taint of residual antebellum thinking that tends to diminish understanding of Fort Monroe's importance not just in American history, but in the history of liberty itself. And if Fort Monroe is less important, then so is respect for its sense of place -- which means condos and the like are OK.

The well-intentioned article above reflects this taint by withholding the dignity of being named from Frank Baker, Sheppard Mallory and James Townsend. In one of the New York Times pieces linked from the article, Adam Goodheart declared of those Black Americans and tens of thousands like them, "Their bold escape, perhaps even more than Abraham Lincoln’s Emancipation Proclamation more than a year later, was responsible for slavery’s extinction."

Yet the usual tired, old telling that’s seen here remains based on the unrecognized, inadvertent but nevertheless condescending assumption that Black people were merely feckless, helpless victims. It still credits instead, and names, the Union general who reacted cleverly and constructively, but who reacted only after other Americans -- self-emancipating Americans -- had acted, and had set history into motion.

Edward L. Ayers has called the events that those Black Americans started "the greatest moment in American history." In the history of liberty itself, that moment makes Fort Monroe important not just for America, but for the planet. It shows America -- the planet’s first nation founded on ideas -- struggling finally to live up to the laws of nature and of nature's god, as proclaimed more than four score years earlier. The Virginia Juneteenth leader Sheri Bailey and I believe that Fort Monroe should be considered for World Heritage Site status. (http://ideas.fmauthority.com/fort-monroe-authority-should-fort-monroe-be...)

But on this planet, Fort Monroe also constitutes some of the most valuable waterfront imaginable. That’s why the Big Money mindset -- following a pattern recognized by Ken Burns in his national parks PBS series, but not recognized in this case by journalists -- forced the perversion of a well-intentioned base-closure law that wasn’t written to account for disposing of a national treasure. That law was written only so that a humdrum Fort Drab in a cornfield, when abandoned, could easily be donated to the city next door for “redevelopment.” That’s a key word in the law, and the key word in Virginia’s leaders’ unwise -- and ironically, financially costly -- outlook on Fort Monroe, which involves de facto partial donation to the city that, after more than three centuries, happened to grow to include the post within its boundaries.

And in effect, that outlook also corrupted not the ethics or the finances, but the judgment, of the National Trust for Historic Preservation and other such organizations, including the particularly feckless Preservation Virginia. The result has been national near-obliviousness to the American cultural disaster now being cemented.

In 2006, the city of Hampton – then, as now, in too much control of the planning for a national treasure that actually belongs to all of us -- conducted public charrettes about Fort Monroe’s future. With their Dover-Kohl consultants, the analogs of today’s Sasaki Associates planning consultants, they brazenly censored -- or tried to, anyway -- all discussion of national park options. Later that year, Hampton and its consultants announced, with brazenness that was by now Orwellian, that the public wanted to blanket the heart of Fort Monroe with condos -- tasteful ones, of course.

This blanketing would have covered the area colored red in the illustration cited above. For propaganda, Hampton and Dover-Kohl publicly polled their advisory committee, which included no private-citizen representatives except from inside Hampton. Among its political members, that official committee included the NTHP’s Robert Nieweg, who sullied his organization’s good name by joining the panel’s unanimous travesty.

NTHP has never wavered from its policy of meek accommodation of Fort Monroe overdevelopment. Recently in a local paper, in fact, an NTHP official’s op-ed began with the falsehood that President Obama designated Fort Monroe as America's newest national monument. But unlike the present NP Traveler piece, that op-ed never got around to revealing and engaging the political controversy over the split in the national monument -- even though the piece appeared right when an election campaign was raging in Hampton, with Fort Monroe a central issue for everyone except one developer-favoring local newspaper. That was the Daily Press, the paper where the NTHP's smarmily disingenuous op-ed appeared.

So here’s the NTHP point again: Without the forceful, unambiguous testimony and insistence of NTHP and other national organizations, the national media will simply not notice that Fort Monroe is getting the equivalent of “redevelopment” on a Monticello hillside. And without some national shaming of Virginia’s leaders, their plan for a mere McFort Monroe appears inevitable.

But even after seven years of seeing how foundationally the Big Money mindset controls Fort Monroe politics, I still have hopes of a miracle. That’s why I hope that everyone who reads this comment will also read a very brief “idea” posting in the Fort Monroe Authority’s online civic discussion: "Please unify nat'l monument by including missing bayfront acres" (http://ideas.fmauthority.com/fort-monroe-authority-describe-what-fort-mo...). If you agree that the national monument should be unified, I hope you’ll register, then “second” (i.e., vote for) that idea, and also maybe contribute a comment. Miracles happen, after all, and none of those who have acted so unwisely are bad people. They're just profoundly wrong to treat a national treasure as a "redevelopment" plum. That’s especially since a _real_ national monument/park will be more enriching anyway -- ironically, including financially enriching.

Thanks very much.

Steven T. Corneliussen, [email protected]

P.S. for NPT editors: All of Fort Monroe matters, not just the moated citadel. So I repeat what I've said to you before: I hope you’ll start using the aerial photo that shows all of Fort Monroe.

Boundary realignments are part and parcel of the National Park System, Steven. When Dinosaur National Monument was first designated, it covered 80 acres. Today, it spans more than 200,000 acres.

The boundaries of Canyonlands National Park long have debated. At one time a monument spanning nearly 4.5 MILLION acres was proposed; today the park encompasses not quite 338,000 acres, but efforts continue to enlarge the park.

There are countless other examples across the system where efforts are ongoing to increase the size of parks. This is not to belittle your complaints, but rather to point out that many park boundaries often are not what they were initially sought to be, but over time efforts such as yours led to more acreage being added.

Thank you Kurt. I've been aware of that for several years. Moreover, it's an argument often advanced by a retired NP superintendent here whom I deeply respect. But I also know what I know, Kurt, and one thing I know is that this situation is unique in several ways. If you'd ever like to learn more about For Monroe, that uniqueness, and what you categorize as my "complaints" -- and thank you for refraining from "belittling" them, however they may be classified -- I'd be glad to talk. It can't be done briefly, though, especially if you have absorbed the smiley-faced view of how we got where we are, the view that portrays Virginia's and Hampton's leaders as civic heroes in this matter. But maybe you haven't. If so, great. Thanks for being interested in any case. Steve Corneliussen, [email protected]

"Fort Monroe was also an active Army base from 1819 until 2011, which makes it the longest serving military installation in our history."

Doesn't West Point count as a military installation? It predates 1819 and, last I knew, was still run by the military.

There are live oaks much further north than Fort Monroe.