Had it not been for one man’s fateful decision, the magnificent old-growth forest of the Congaree River floodplain would have been destroyed long ago. In the early 1900s, a timber tycoon decided to put his vast holdings of South Carolina forestland in timber reserve status. Six decades later, thousands of acres of the old-growth trees were preserved in Congaree Swamp National Monument, today’s Congaree National Park.

In the 1890s and early 1900s, Chicagoan Francis Beidler acquired hundreds of thousands of acres of forested land in South Carolina. The regional economy was depressed at the time, so timber land was bargain-priced. Beidler bought some of his properties for as little as two dollars an acre at sheriff’s auctions.

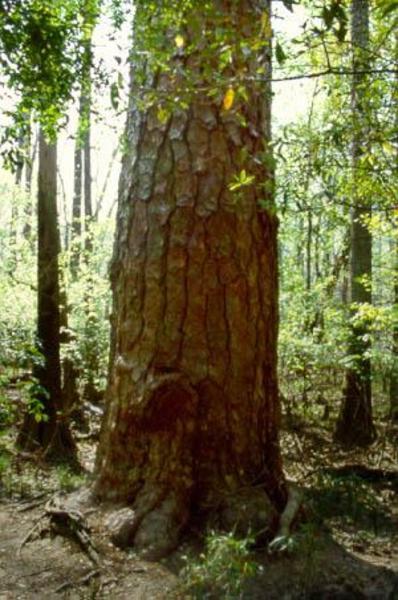

Among Beidler’s holdings were tens of thousands of acres of old-growth forest in the Congaree Swamp, which is situated near Columbia and the geographic center of the state. Though dubbed a swamp, the ecosystem occupying the flood plain of the Congaree River is more properly termed a river bottom hardwood forest. The river spills out of its banks and occupies parts of the floodplain episodically about ten times a year; there are also areas that remain wet or very soggy most of the time. Bald cypress and tupelo dominate the wetter areas, while the balance is a mixture of more than 80 other tree species, including sweetgum, various oaks, and even loblolly pine.

When Beidler bought his Congaree land, completing his purchases by 1905, he acquired commercially desirable trees in almost mind-boggling numbers. The bald cypress trees alone (some of which were more than 20 feet in circumference) were worth far more than he paid for the land.

Beidler may have found it easy and cheap to acquire a lot of valuable timber in South Carolina, but he soon discovered that turning these assets into money was an entirely different matter. This shrewd businessman soon found himself up to his ears in problems related to harvesting, transporting, milling and marketing his timber.

Beidler’s Santee River Cypress Lumber Company’s harvested logs from the Congaree Swamp for a number of years, but found it hellishly difficult and basically unprofitable. Had there been a logging difficulty scale of the early 1900s with the numeral one for “very easy,” then logging in the Congaree Swamp would probably have rated at least an 8.5. Hot and humid weather, frequent flooding, the lack of all weather roads, the unavoidable use of labor-intensive methods, and other factors combined to inhibit access and make the timbering and transport operations very complicated.

Most logging occurred close to the river and along and near the sloughs or “guts” (intermittent watercourses). The basic idea was that logs harvested there could be floated downriver for processing at the company’s Ferguson mill (a site now flooded by Lake Marion).

The logging and milling crews were inefficient. In addition to working under arduous conditions that modern workers wouldn’t accept, they were ridden with malaria and various other chronic, debilitating diseases. Getting heavy cypress logs out of the swamp and floating them down the river to the sawmill was a chancy undertaking. Even though the logging crews killed the cypress trees (by girdling the bark) and dried them while standing, many cypress logs were too heavy to float and had to be left behind.

By about 1915, the Santee River Cypress Lumber Company had abandoned its logging operation in the Congaree. Large tracts of old-growth timber, including more than 10,000 acres in the center of Beidler’s Congaree tract, had been left almost completely untouched.

It was decision time for Francis Beidler. Had he possessed the robber baron mentality so common in his contemporaries, he would have sold his South Carolina timber holdings and moved on to easier pickings. But Beidler was a conservationist who thought far ahead. He knew that old-growth trees were being cut at a rapid clip and reasoned that his bald cypress, sweetgums, oaks, and other trees would grow in value as other forests were cut down and good timber grew harder to get. So, instead of selling his holdings he just hung on to them – or, as some have termed it, he placed them in “timber reserve” status.

Francis Beidler, Sr. (there’s a Junior now) died long ago and willed his South Carolina forestlands to surviving family members. The Santee River Cypress Lumber Company he established still exists.

Beidler’s conservationist approach to forest utilization proved very fortuitous. If he hadn’t placed many thousands of acres of uncut trees in timber reserve on the Congaree floodplain nearly a century ago, there would have been no magnificent forest left to be preserved in a national park.

Protection did not come without a struggle. In the 1960s, foresters counseled the Beidler heirs that their Congaree Swamp trees were “overmature” (growing very slowly) and should be harvested. In 1969, high timber prices prompted the Beidler heirs to resume logging operations in the Congaree Swamp. On the advice of their consulting foresters, the heirs decided to harvest the forest on a sustainable-yield basis with the intention of replacing the old-growth, biologically diverse forest with even-aged stands of trees consisting of just a few species. Pines were to be logged on a 30-year cycle (about 500 acres a year) and large diameter veneer-grade hardwoods like sweetgums and oaks were to be cut on a 50-year cycle.

By the late 1960s all the large tracts of river bottom hardwood forest in the Southeast had been obliterated except for the Beidler Tract on the Congaree floodplain. The more than 10,000-acre uncut tract was like a living dinosaur, and some who were awed by its record-size trees were prompted to call it “Redwoods East.”

Logging now began to chew away at Redwoods East. Seeing the damage caused by renewed logging, and knowing that the old-growth forest and its record trees would soon be obliterated, concerned local citizens initiated a grassroots campaign to save the floodplain forest by making it a unit of the national park system.

The concerned citizens who formed the Congaree Swamp National Preserve Association in the early 1970s were following through on policies that Harry Hampton began calling for in the 1950s. Hampton, a local newspaperman, was an avid hunter and conservationist with a deep and abiding love for the Congaree Swamp. He believed that the virgin forest of the Congaree Swamp should be preserved, and concluded that the only sure way to make that happen would be to bring it under federal protection.

The citizen action proved effective, despite fierce opposition from stakeholders such as the timber industry, local property owners, and the Cedar Creek Hunt Club (which leased Beidler Tract hunting rights). Don’t feel sorry for the Beidler heirs. They sold their Beidler Tract holding to the Federal government for more than $30 million, receiving some very nice tax breaks and psychic income in the bargain. Unfortunately, about 2,500 acres of the Beidler Tract were logged before the cutting could be halted.

On October 18, 1976, President Gerald Ford signed legislation establishing Congaree Swamp National Monument. Redesignated Congaree National Park in 2004, and now encompassing more than 25,000 acres, the park is renowned for its extensive old-growth forest, remarkable biodiversity, and big trees (including some state and national champions). The park attracted 115,000 visitors last year.

Postscript: Congaree National Park has paid homage to the people who fought to protect the old-growth forest of the Congaree River floodplain. The park’s gorgeous visitor center is named in honor of Harry Hampton. A forest giant has been named the Jim Elder Cypress is honor of the man (then a local high school teacher) who led the grassroots campaign to save the Beidler Tract and get it preserved as a national park. Dick Watkins, who has worked tirelessly in behalf of Congaree Swamp interests for more than 35 years, received the prestigious Marjory Stoneman Douglas Award in 2003. If you watch the introductory film in the park auditorium, you’ll see interviews with Congaree friends like LaBruce “Brusi” Alexander and John Cely. What about Francis Beidler? He is mentioned only in passing, including a single sentence on the park's website, and with little appreciation for the vital role he played. It just goes to show you something or other.

BTW, the one conspicuous public monument to Francis Beidler the conservationist is the Francis Beidler Forest in the Four Holes Swamp in Dorchester County. Containing one of the largest remaining stands of virgin, old-growth bald cypress and tupelo gum (around 1,800 acres), the 15,000-acre Francis Beidler Forest is owned and operated by the Audubon Society.

Comments

I have some limited photos that I can share.

I preparedabook manuscript, but no publisher has had an interest so far.

I am an underwater logger and have a great interest in the history of early logging in South Carolina. I am thinking of setting aside some space in a building I am in the process of securing for a little museum dedicated to the subject. If any of you would be willing to donate information or copies of early photos etc please contact me so we can investigate this idea further. Thanks!

I am doing a project on the Congaree Swamp and is curious about Santee River Cypress Company. I wanting to know more about Beidler's involvement with the Congaree Swamp. Do you still have any pictures or artifacts from the time or any journal? Why was the company interested in the area, to begin with even though it was a swamp? Was it because it was purchased so cheaply? Why did the company stop logging in the area? why did Beidler decide to preserve and protect the area? you can contact me at [email protected].

Thanks.

Sutton, the article adresses why the company was interestd in the area - the massive trees that existed in the swamp, such as cypress, and other bottomland hardwoods. they were able to acquire a lot of land on the cheap because the area wasnt considerd suitable for any other purpose, swamps were fair game for development , and had been for decades prior to this, Abraham Lincoln was involved in some railroad cases involving swampland in the 1840s and 50s in Illinois. Congaree is one of the few surviving remanants of what much of the South looked like prior to settlement- large swamps and huge forests. you can see similar hardwods in the national forests in Mississippi. the company stopped logging, because it was uneconomic to keep logging at that point, and while many other timber barons would have simply passed the holdings to someone else who would keep whittling away, Biedler felt that some of it should be left for posterity. some of it eventually was, in the 1970s, but likely not as much as he would have wanted, thanks to his heirs not appreciating what they had.

our park system didnt just spring into existence overnight, the 61 parks we have today were the product of decades of efffort, in some cases it took over 100 years for an area to get park status, such as Pinnacles in California, which got park status in 2013 after 105 years as a monument, or Indiana dunes in Indiana , who just got park status this year after being proposed as a park in 1916. Nor by any means are all the worthy areas protected, there are literally hundreds of other places across the country deserving of national park or monument status- Bristol Bay in Alaska, The San Rafeal Swell in Utah, Boulder White Clouds in Idaho, la Bajada mesa in new mexico, Lake Tahoe in Nevada, Mount Hood and Owyhee Canyonlands in Oregon and Niagara Falls in New York, just to name a few.

Every state and teritory has areas that merit that status, unfortunately Congress doesnt act quickly on things like this at the best of times, normally its left to the president to declare them as monuments under the Antiquities Act. Obama did that a lot, his 29 new monuments were a record for any president, but Trump hasnt shown much interest in conservation, hes only declared 1 monument- Camp Nelson in Kentucky- and tried to massively reduce monuments in Utah created by Clinton and Obama. Fortunately, he'll lose in court on that, and be barred from trying to shrink any other monuments going forward. it is left to Congress to grant an area park status, and they have only added 3 since 2010- Pinnacles , Gateway Arch and Indiana dunes. If you go back to 2000, they've added 6 , including Congaree in 2003, and the number becomes 11 if you go back to 1990. in short its not something Congress does that often.

In looking through old newspapers, I found a story about an employee at Ferguson who was to lift up a footbridge at the mill when a train of fresh lumber was taken out to a switch yard to partly cure. The railroad at Ferguson was an electric third rail operation, and may be the only third rail railroad south of Washington, DC. The employee stepped on the rail and was electrocuted.

While this was a terrible occurrance, it provides a view about the lumber trains that no one has mentioned and is long forgotten.

The newspaper was the Orangeburg paper, and it regularly wrote up events at Ferguson.

If you find something really unique, let me know.

My book manuscriprt on the Santee River Cypress Lumber Company has not attracted a publisher.

My SCETV program that I wrote and directed took an interesting section to ride in a small boat out to the Kilns at Ferguson, but at one point the water got choppy and some splashed over the sidewalls. I cancelled the trip and we returned to the beach.

A highlight was riding in a CSX freight from North Charleston to Lanes and then the length of the Central Railroad of South Carolina through Mullins and Alcolu to Sumter. SCETV reports the tape was lost.

Tom Fetters

I don't recall encountering the phrase "underwater logging" before. It sounds fascinating and hazardous.

Just visited the Beidler Forest Preserve.....nice that the family and others saved this tract. Congrats also to National Audubon for preserving and managing it as well. We need more places like this, even if they are not old-growth.