As the first major step towards reaching its goal to “conserve, connect, and restore” 30 percent of the nation’s land and water by 2030, the Biden administration released its “America the Beautiful” report in 2021, laying out the broad principles guiding the effort, but lacking specific details on which lands, exactly, need to be conserved. Despite this lack of details, though, it’s clear “America the Beautiful” will rely heavily on the National Park Service.

While it’s easy to imagine reaching 30 percent simply by expanding the vast park units in the West, that doesn’t do a whole lot of good for the millions of people, plants, and animals in the East.

“The answer is a web of sites across the entire country, it’s not one big area somewhere,” Dr. Mark Anderson, director of conservation science at The Nature Conservancy told the Traveler in a recent interview.

Luckily, there is more room for parks to grow in the East than you might think.

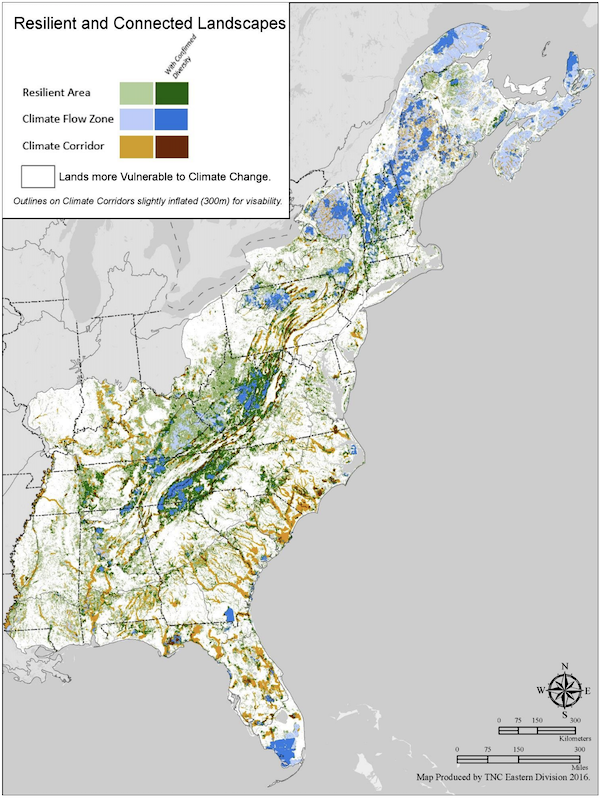

Dr. Anderson led a team at the Conservancy that created the Resilient and Connected Lands Network. The network identified areas high in “landscape diversity” and “local connectedness.” Diverse landscapes with a range of topography and elevation provide protection against a wide variety of threats: high ground to avoid floods, shade to avoid heat, berries to eat when the fish population is low; and as climate change forces animals to migrate to find suitable habitat, it’s critical they have a path of connected lands to get there.

Lands that are diverse and connected are the “most likely to remain resilient” to climate change, Dr. Anderson said.

Using the Conservancy’s Resilient and Connected Lands Network, the Traveler identified several parks that are in or directly adjacent to resilient lands and have existing authority to acquire more land without additional congressional approval (notoriously slow), thus making them prime targets for further expansion.

Two of those sites are the Blue Ridge Parkway –- a 469-mile scenic road coursing through North Carolina and Virginia -– and Great Smoky Mountains National Park, at the Parkway’s terminus in North Carolina.

The sweeping forests the parks protect store vast amounts of carbon dioxide, provide a critical wildlife corridor for millions of birds and other animals, and protect one of the largest watersheds on the East Coast.

The main force driving any park unit’s ability to acquire and protect more land is that park’s enabling legislation. Some parks are given strict boundaries they cannot grow beyond. Others, like Great Smoky, are more flexible. When Great Smoky was established in 1940, it was authorized to be up to 750,000 acres, but today it stands at only 522,000 acres due to existing privately owned land within the park’s boundaries. Assuming owners are willing to sell and the land meets park criteria, the park could have more than 225,000 acres of room to grow.

According to Phil Francis, former superintendent at Blue Ridge Parkway and Great Smoky Mountains and the outgoing chair of the Coalition to Protect America’s National Parks, there are more than 4,000 individual landowners adjacent to park lands. With that many different landowners, there’s no one size fits all answer.

“We have a toolbox we can choose from: conservation easements, donations, acquisitions,” he told the Traveler.

Blue Ridge Parkway, by its enabling legislation, is authorized to acquire lands that are contiguous with current parkland, meet the park’s protection objectives, and, of course, have a willing seller, current parkway Superintendent Tracy Swartout told the Traveler in an earlier interview.

Even if the seller is willing, they may not be realistic. “I got a call

once,” Francis laughed, “from someone who wanted to sell 3,000 pristine acres to Great Smoky. And when I asked him how much he wanted for it, his price was higher than the land acquisition budget for the entire National Park Service.”

While that particular price might have been unworkable, the fact is, until very recently, funding for land acquisition has been sorely lacking. “The Park Service has a list of needs,” Francis said, “but we haven’t seen the money allocated.”

That is starting to change. The Land and Water Conservation Fund is the main source parks use to acquire lands and the Great American Outdoors Act, passed in 2020, guarantees it at least $900 million in annual funding. That funding allows parks a level of certainty they haven’t had before and is a “game changer,” says Amy Lindholm, Land and Water Conservation Fund Coalition manager and northeast regional coordinator at the Appalachian Mountain Club.

As important as funding is, it doesn’t magically solve all of the Park Service’s problems. As the Traveler has documented, major projects, like acquiring new lands, can take years to complete, and the Service is plagued by a lack of personnel.

In fact, almost every person the Traveler spoke to for this article identified the length of the acquisition process -– and specifically the appraisal step -– as the second biggest hurdle to protecting more land, after a lack of funding. When the Traveler asked the Park Service what it is doing to address the issue, a spokesperson offered no specific plans. "Under current Department of the Interior policy, the Department’s Appraisal and Valuation Services Office is responsible for all appraisal and valuation services," the agency said in an email. "NPS is currently working with AVSO and others in the department to identify impediments and recommend solutions that may improve the timeliness of receiving appraisal delivery."

But if the Park Service can work to overcome these challenges, the rewards are plenty: according to The Nature Conservancy, the Eastern resilient lands network “contains over 80,000 known rare species… stores 56 percent of the region's carbon and contains 75 percent of the high value water supply land.”

Sometimes, when a park doesn’t have expansion authority, more creative solutions are required. The proposed Chesapeake National Recreation Area would combine existing park units (and potentially acquire more land in the future) to create a unified national recreation area -– a unique solution to the problem of fragmentation in the east, says one of the many folks working on the proposal, Pam Goddard, Mid-Atlantic senior program director at the National Parks Conservation Association. “We’re looking at already protected areas and where we can plug the holes and make the entire area stronger.

There are acres that could be added to Great Smoky Mountains National Park, but they're expensive/NPS file

“Parks in the West have vast amounts of land they could acquire," she continued. "In the East, we’re looking at critical, small expansions. Looking at landscape connectivity and wildlife corridors.”

This proposal is different from others listed here: it would require congressional authorization. Senator Chris Van Hollen (D-MD) is leading the charge. In a statement to the Traveler, he said, “The Chesapeake Bay is a national treasure with natural, cultural, historical, and recreational significance…. This designation will bolster our efforts to protect and focus more federal resources on restoring the Bay while boosting tourism and supporting our Bay economy.”

A "Chesapeake National Recreation Area" would greatly expand the National Park System/NFWF

The Biden Administration has a short timeline and a narrow path to reach its conservation goals. But, as Goddard put it, “History doesn’t stand still. We need to be nimble when the opportunity arises or else tomorrow it’ll all be condos.”

Traveler postscript: For more on this topic, listen to this podcast from National Parks Traveler.

Comments

Those in washington need to expand the parks in the east!!!! I'm glad someone is doign something about it!!!!!

Thank you for raising these important issues. You are absolutely correct in stressing that we need to ramp up public acquisition. This is especially true in the East, South, and Midwest, where existing public lands are sparse and poorly connected.

We should also be providing better protection for existing public lands, such as national and state forests, which we already own. Most of these lands now allow logging and other resource extraction, which worsens climate change, degrades forest habitats, and harms critical green spaces needed by people. There are millions of acres of national forest land in the East which could be transferred to the National Park Service, which does not allow resource extraction.

This approach could be used to expxand 500,000-acre Great Smoky Mountains National Park. The park is adjacent to the Cherokee, Nantahala, and Pisgah national forests. A National Academy of Sciences paper found that logging and other extractive uses are fragmenting and degrading the ecosystems of these national forests.

https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1418034112

Great Smoky Mountains National Park could be expanded to 2 million acres by incorporating lands from these national forests. This would ensure their strong and permanent protection and connect the existing park to wilderness areas and other core wildlands in the region.

Great article. Much needed viewpoint, especially here in the Smokies where commercial, Sevier county interests Trump conservation. The wildfires were a warning to greedy landowners. I fear that the Smokies will be like central park in less than twenty years, a great pocket wilderness ringed by go kart tracks, Blacberry Farms commercial enterprises who feed like lampreys off this special place.

The Article, "Room to Grow? For Parks in the Eastern U.S, More than You Realize", is a well written article, about the opportunity for the Park Service to grow. But the article misses one important point. The past and current management in the Park Service does not want to grow. When I worked for the Park Service, I would often hear from Senior Management, "We don't want any more parks, we can't take care of what we have." Senior Management claimed that the large "backog maintenance" was created because the Park Service had acquired to many improved properties. Management used the two light houses that NPS accquired at Pictured Rocks as an example. (It is going to cost too much to retore them, although Congress authorized the acquisitions) Today, many Senior Management posiitions are still held by employees that still hold this position. Certainly Director Sams brings new life and vision to the Park Service but he has retained the old "no growth" management staff.

For example at the end of the last Administration, Park Senior management started to implement an "Investment Review Board." (IRB) This board, essentially would stop any new land acquisistons of improved properties unless the Park had the funds to remove or maintain the structures. After President Biden came into office and after he announced the 30 percent by 2030 goal, the "carryover" management staff implemented the Investment Review Board. After an outcry from non-profit conservation groups implementation of the IRB was "suspended." It is still on the books?? The IRB was even opposed to the acquisition of historical structures that Congress authorized. The staff that implemented the IRB is still on the Park Service payroll?

Certainly the Park Service has a "backlog" maintenance issue. But it was NOT caused by the acquisition of $10-11 billion dollars worth of improved properties. (The $10-11 billion is the current maintenance backlog number) The "backlog" maintenance issue is caused by Administrations not requesting adequate funds for Park Maintenance and/or Congress not appropriating the funds. Second, the Park Service continues to request funds to build new visitor centers/camp grounds and roads. Every "new park" does not need a $30-50 million visitor center or large RV campgrounds. The Park Service need not build visitor centers to attact people to parks. One of the most greatly used Parks is the Appalachian Trail. It is used for hiking. There are no million dollar visitor centers and certainly no RV campgrounds. Public roads that cross the Appalachian Trail are often block with hikers' cars. They come with good hiking boots, a bottle of water and a walking stick.

Director Sams has only 3 years or less to change the direction of the Park Service in order to meet President Biden 30/30 goal. Maybe a new Agency should be establshed to "conserve, connect and restore the nations's land and water." With the current NPS management staff, Director Sams is not going to get the job done. Sometimes it is necessary to buy new furniture for one's home instead of keeping the old broken stuff.

Howard, while I agree some funds are not well spent, I can't argue with the thinking that we shouldn't buy things we can't afford. It's easy to say the "maintenance issue is caused by Administrations not requesting adequate funds for Park Maintenance and/or Congress not appropriating the funds" but the fact is it isn't a priority for most the public. Certainly not at the expense of any of the freebees they get from the government now.

Buck, the elementary school tool of diagraming sentences --- applied to your post here minimizes the headaches from reading it, a slight bit. Special extra credit for diagramming all of your "not"s, what they negate directly and indirectly in the full rhetoric, and how that all adds up semantically, is an adventure in semantic obfuscation. Truly an expert at work.

Thank you!

I don't understand your desire to attack ecbuck, Rick. He made a valid argument, I believe. I complain, continually, that the government and the media use their power and influence to reduce my hope for the protection of wilderness. Instead, I must use what money I have after taxation and give to charities that have to use it to influence the government and the media. This is a long and hard endeavor. I wish I had control over my tax payments to the governments that are insatiable and inept. Nature First.

There is no room to grow for more parks in the east. I for one prefer the free forests that we have now. The parks are no longer eglaitarian and are instead a luxury for the wealthy classes. Also- the "thirty by thiry" plan is an IMF idea that has nothing to do with conservation and everything to do with blocking development, increaseing housing costs, and "herding" the poor into high cost "affordable" apts in the cities that are owned by the people pushing this plan. heck- Joe biden has three houses. Perhaps he can donate two for the plan